India Uncut

This blog has moved to its own domain. Please visit IndiaUncut.com for the all-new India

Uncut and bookmark it. The new site has much more content and some new sections, and you can read about them here and here. You can subscribe to full RSS feeds of all the sections from here.

This blogspot site will no longer be updated, except in case of emergencies, if the main site suffers a prolonged outage. Thanks - Amit.

Monday, February 27, 2006

Further adventures of Ponty Manesar

You can't keep a good Ponty down. The series that started here continues, so here are some more adventures of the noble Ponty Manesar that young Jamie Alter and I conjured up in Baroda. Needless to say, these are utterly fabricated.

* * * *

Ponty is bowling to the great Australian, Micky Monting. Monting waits in his crease as Ponty runs in, the air as thick as desi ghee with tension. Ponty jumps in his crease and moves through the delivery motion. Monting steps on the front foot, then freezes in bewilderment. No ball has emerged out of Ponty's hand.

Ponty turns around and appeals madly.

The umpire isn't amused. "What the fuck are you appealing for?" he asks.

"The ball," says Ponty, imploringly. "Can I have the ball please?"

* * *

As a team-bonding exercise, Duncan Fletcher decides that the team should play basketball. Ponty has never played basketball before. Nevertheless, he rushes out manfully onto the basketball court. Then the ball is thrown to him, and he just stands there, unsure of what to do with it.

"Bounce, Ponty, bounce," shouts Shaun Udal.

Ponty keeps holding the ball and starts jumping up and down.

* * *

Ponty sees that a number of Indian players have started restaurants. He starts one as well, in Mumbai's five-and-a-half Bungalows area. It's called Urban Patka, and the lentils there are called uDal. (Reference.)

* * *

Ponty loses his place in the side because his room-mate, Shaun Udal, complains about his appealing in his sleep. The official broadcasters for the series take him on as a commentator, though. His first assignment is to do a pitch report before the first Test begins. Ponty walks out to the middle with a key in his hand.

"Let us see how hard the pitch is," says Ponty to camera, "and how the cracks in it may develop." He bends down and sticks the key into a crack. It slips from his hands.

"Oh bloody," he thinks. "Oh blooda. I can't lose my key like this. How will I open my suitcase to change my patka?"

So Ponty digs a finger into the crack. Ah, he feels the key. He curves his finger against it and tries to push it out. But the crack widens, and the key goes deeper.

He slips in a second finger and digs frantically, trying to get a grip on the key. The key keeps slipping deeper and deeper. A third finger goes in, and then his hand starts creeping in. Soon his entire hand, up to his wrist is in the pitch.

No luck.

Ponty realises that he has a hardback Samsonite that he cannot open without the key. His patkas! He starts digging madly, and soon his entire arm is in the pitch, upto the armpit. He feels ticklish.

Then he manages to grab the key! He pulls it out and stands up.

There is a huge crater on the pitch now, on a good-length spot. Everybody looks at the pitch in shock and horror. Then they notice Ponty. His arm is raised above his head, holding the key.

"Found it," he cries in delight. "I've found my key."

* * * *

Ponty is bowling to the great Australian, Micky Monting. Monting waits in his crease as Ponty runs in, the air as thick as desi ghee with tension. Ponty jumps in his crease and moves through the delivery motion. Monting steps on the front foot, then freezes in bewilderment. No ball has emerged out of Ponty's hand.

Ponty turns around and appeals madly.

The umpire isn't amused. "What the fuck are you appealing for?" he asks.

"The ball," says Ponty, imploringly. "Can I have the ball please?"

* * *

As a team-bonding exercise, Duncan Fletcher decides that the team should play basketball. Ponty has never played basketball before. Nevertheless, he rushes out manfully onto the basketball court. Then the ball is thrown to him, and he just stands there, unsure of what to do with it.

"Bounce, Ponty, bounce," shouts Shaun Udal.

Ponty keeps holding the ball and starts jumping up and down.

* * *

Ponty sees that a number of Indian players have started restaurants. He starts one as well, in Mumbai's five-and-a-half Bungalows area. It's called Urban Patka, and the lentils there are called uDal. (Reference.)

* * *

Ponty loses his place in the side because his room-mate, Shaun Udal, complains about his appealing in his sleep. The official broadcasters for the series take him on as a commentator, though. His first assignment is to do a pitch report before the first Test begins. Ponty walks out to the middle with a key in his hand.

"Let us see how hard the pitch is," says Ponty to camera, "and how the cracks in it may develop." He bends down and sticks the key into a crack. It slips from his hands.

"Oh bloody," he thinks. "Oh blooda. I can't lose my key like this. How will I open my suitcase to change my patka?"

So Ponty digs a finger into the crack. Ah, he feels the key. He curves his finger against it and tries to push it out. But the crack widens, and the key goes deeper.

He slips in a second finger and digs frantically, trying to get a grip on the key. The key keeps slipping deeper and deeper. A third finger goes in, and then his hand starts creeping in. Soon his entire hand, up to his wrist is in the pitch.

No luck.

Ponty realises that he has a hardback Samsonite that he cannot open without the key. His patkas! He starts digging madly, and soon his entire arm is in the pitch, upto the armpit. He feels ticklish.

Then he manages to grab the key! He pulls it out and stands up.

There is a huge crater on the pitch now, on a good-length spot. Everybody looks at the pitch in shock and horror. Then they notice Ponty. His arm is raised above his head, holding the key.

"Found it," he cries in delight. "I've found my key."

Reacting to baby pictures

Via Jai, I come across this excellent primer by Falstaff. Immense merit resides.

Welcome, Amitava Kumar

One of the characteristics of Amitava Kumar's writing is that he doesn't flinch from the personal, and you'd think that he would make an excellent blogger. Well, he does. The writer of books such as "Passport Photos ," "Bombay-London-New York

," "Bombay-London-New York " and "Husband of a Fanatic

" and "Husband of a Fanatic " has started blogging, and India Uncut welcomes him to the party.

" has started blogging, and India Uncut welcomes him to the party.

And what better way to check out his blog that to begin with an open letter, "Lalu Yadav to George Bush."

Crash

Despite buying around 50 DVDs during my travels through Pakistan, I hadn't actually seen a single film this year until yesterday, when I finally returned to Mumbai from Baroda. My DVD player is misbehaving these days, and we went off to Fame Malad to watch "Crash." We could hardly have made a better choice.

"Crash," directed by Paul Haggis, is an ensemble film, with various interweaving storylines, much like Robert Altman's "Nashville " (which I loved) and "Short Cuts

" (which I loved) and "Short Cuts " (which didn't live up to my expectations from reading the stories and seeing Altman's previous work), but crisper, tauter, and more packed with emotion. There are some remarkable set pieces in the film, and continuous build-ups and releases of dramatic tension. There isn't a wasted moment through it all, and characters are established with both economy and depth, sparking both recognition and introspection. The cinematography and the background score are wonderful, expressive but unindulgent.

" (which didn't live up to my expectations from reading the stories and seeing Altman's previous work), but crisper, tauter, and more packed with emotion. There are some remarkable set pieces in the film, and continuous build-ups and releases of dramatic tension. There isn't a wasted moment through it all, and characters are established with both economy and depth, sparking both recognition and introspection. The cinematography and the background score are wonderful, expressive but unindulgent.

The theme of the film is how we tend to stay cocooned in our own little worlds, and are suspicious of those outside it. All the characters in this film crash through those barriers, and are forced to re-evaluate themselves and the worlds they inhabit. "Crash" has been praised as being an acute picture of race in America, but like all great films, it speaks to everyone, and to the condition we all share.

I won't elaborate much on plot -- this is not meant to be a review -- but do go out and watch the film . It's outstanding.

. It's outstanding.

PS: Here are reviews of "Crash" by David Denby and Roger Ebert.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

On open-air press boxes

They're great because they give you a sense of how the crowd's feeling and what the weather is like and you get a sense of being part of the action. An AC press box insulates you from all that, and you're halfway to not being at the ground. On the other hand...

... On the other hand, it's bloody hot.

Friday, February 24, 2006

The mall and the mandi

Going around Alkapuri in Baroda last evening, I passed several malls, and all of them looked the same. There was, at a lower level than the main road, a courtyard surrounded by stores on either sides, leading to a large U-shaped apartment complex at the end, with offices and stores on multiple levels. The courtyard had motorcycle parking in the middle, walking space along it, and two to four levels of shops on either side. It was like a design template, and many malls on that road, all of which would begin shutting down between 8.30 and 9 pm, looked just like that. Here's a pic of one such:

Two nights back, I had dinner with some friends in some another part of Baroda, and their house was in an apartment complex opposite a sabzi mandi (vegetable market). Although their flat faced the other direction, a fair bit of noise from the market filtered into their apartment. It sounded like people rioting. Given what this city has been through in the last few years, it was a disconcerting sound.

The adventures of Ponty Manesar

An even bigger question than “How does one entertain oneself in small towns?” is “How does one wake up early in small towns?” Yesterday, the first day of the tour game between England and the Board President’s XI, I had trouble rousing myself out of bed, as did my room-mate, young Jamie Alter from Cricinfo. What finally woke us up was a series of fine adventures we concocted around Ponty Manesar – as we call this feller.

The previous day young Jamie had watched Ponty drop a few catches in the nets, and Ponty had seemed to be rather hapless, the kind of young man who gets ragged by his team-mates and suchlike. Plus, he’s a surd. So we imagined a number of situations in which Ponty finds himself, which are all very PJ-like, but we rather enjoyed some of them, so why not blog them? I’d like to emphasize that neither of us have met Ponty, and all these stories are entirely fictional. Also, if Monty is reading this, apologies! Here we go:

* * * *

Ponty Manesar shares a room with Shaun Udal, one of his spin rivals in the England team. Udal notes that Ponty is not too good at taking catches. So he decides to tire his rival out the night before a game. He buys a crazy ball, and says to Ponty, “Catch, Ponty!” Then he throws the crazy ball at a wall, and as it bounces from wall to wall, young Ponty runs around madly trying to catch it, arms and legs flailing here and there. Every once in a while, Udal throws another crazy ball at a wall and shouts, “catch, Ponty!”

* * *

Ponty is appealing in his sleep (verb, not adjective) when Udal, disturbed by the noise, shakes him awake and says “Ponty, keep it down!” Then he turns and goes back to sleep.

Poor Ponty wonders what it is that Udal wants him to keep down. He looks all around him and, not finding anything else, puts the phone on the floor.

* * *

A few minutes later, an idea strikes Ponty: Udal is his rival for a place in the side, and here’s Ponty’s chance to make him ill so he can’t play. Ponty gets up and puts on thermal underwear. Then he wears his thickest shirt, and a pair of corduroy trousers. Then he puts on a sweater, a jacket and a monkey cap over his patka. Then he lowers the AC temperature as far as it will go and gets into bed, and waits for Udal to fall ill.

After five minutes Ponty is asleep. Udal wakes up and feels a bit cold. He turns off the AC. Then he looks at Ponty, sees the way he’s dressed, shakes his head sadly, and goes to sleep.

* * *

Udal is chatting with Ponty in the morning. “Plunkett has an inferiority complex,” he says, “and Vaughany has a superiority complex.”

“That’s nothing,” says Ponty. “My uncle in Ludhiana has a shopping complex.”

* * *

That morning when young Jamie and I are on our way to the stadium, we see Ponty on a stationary bicycle in the middle of the highway. We stop to say hello.

“Arre, stadium kahan hai?” he asks.

We point the way.

“Thanks,” he says, and starts cycling faster than ever.

* * * *

Somebody asks Ponty what his favourite TV show is. He says:

“Ponty Mython.”

* * *

Michael Vaughan decides that as this is a practice game, he wants to see both Udal and Ponty in action at the same time. He decides that they will bowl at the same time from the same end. He explains this to them.

“Shaun, you will bowl over the wicket,” he says, “and you, Ponty…”

“I know, I know,” says Ponty. “I will bowl under the wicket.”

* * *

Ponty, when tying his patka in the morning, accidently picks up a pink saree that happens to be lying around in the room, and uses that for his patka. Later in the day, he is fielding at midwicket, and a ball is hit past him towards the boundary. As he chases it, his patka starts unravelling. As he runs from midwicket to deep midwicket, a train of pink chiffon forms behind him.

* * *

Jamie and I are at a shopping complex in Alkapuri in Baroda when we come across a shop called Pinky’s. Instantly we call the Taj Hotel where Ponty is staying and give them a PR idea. The next morning, they conduct a special presentation for Ponty. They are going to unveil a painting for him, they say.

Duncan Fletcher goes backstage before the show to see what the painting is. They unveil it. It shows Ponty in a pink patka, and is titled, Ponty’s Pink Patka. “It alliterates, sir,” the PR manager explains. “A blogger gave us this idea.”

“But his name isn’t Ponty,” Fletcher points out. “It’s Monty.”

The hotel guys scratch their heads and call the painter. He changes the painting. They call it Monty’s Mink Matka, and also present him with a matka made of mink.

* * * *

Young Jamie, Ponty and I are strolling in the evening at Alkapuri when we see a store called “Aradhana Dresses.” Ponty gets very excited and rushes in. He looks here and there, almost jumping around. The storekeeper asks him what he wants.

“The sign outside said Aradhana Dresses,” Ponty says. “I’d really like to see her when she dresses. Please please please.”

* * *

Ponty enters a stationery shop with us and refuses to move.

* * *

Ponty drops us off to our hotel, and in the lobby, he sees a sign that says “Ladies.” Instantly he rushes in there. A manager rushes behind him and asks him what he wants.

“Ladies,” he says, sheepishly.

* * *

The next morning, because the Englishmen are a long way from home and some of them have started bothering Ponty, who at least has long hair, the families of the players join them. The team bus goes to the airport to get them, and brings them to the team hotel, where the team is waiting.

One by one the players’ wives and girlfriends emerge. Finally, at the end, emerges Ponty’s aunt from Patiala. (“Harvinder aunty!” he exclaims.) Then his uncle from Ludhiana. (“Harvinder uncle!”) Then his 16 cousins from Amritsar and his four grandparents from Bhatinda. And so on.

When all 29 have emerged from the bus, Ponty turns to Udal and says, “Mate, sorry, I forgot to make hotel bookings for them, they’ll be staying in our room.”

* * *

Ponty becomes a star in India, and gets an offer to play the lead role in a porn film. He accepts, rather excited at the idea.

“And what would you like to call yourself?” the director asks him. He replies:

“Pondy Manesar.”

I aspire to be a dental plosive...

... and wish to meet fricatives, with whom I can produce affricates.

You can read all about me here.

(Link via email from MadMan.)

He gave me all his soap

Priyanka Joseph points to an article where a Korean comfort woman talks about a kamikaze pilot who "repeatedly raped her" and then fell in love with her and made up a song that helped her survive. Who felt the greater sadness, I wonder: the man who knew he was going to die, or the woman who knew she would have to live like this?

Thursday, February 23, 2006

The secret behind Mallu names

For the sake of justice

Jessica Lal didn't get it. But you can help ensure that Manjunath Shanmugam does. Click here for details.

The charms of Neenjari

I'm at the IPCL ground in Baroda, where England is playing the Board President's XI, and we were told in the morning that Michael Vaughan would not be playing the game because of a knee injury. Instantly the thought came to mind that 'knee injury' doesn't quite glide off the tongue, requiring an unpleasantly forced pause between 'knee' and 'injury'. In fact, any combination of two words where the first ends with a vowel and the second starts with one faces this problem. Why not combine those words then, eliminating one of the vowels?

Thus, 'knee injury' would become 'neenjari', 'toe injury' would become 'tonjari' and so on. You could even use this trick for phrases that involve a consonant, as long as the neologism doesn't confuse. For example, what else could an earjury be but an ear injury. In the case of long words, entire syllables could be removed, as a hamstring injury could become, simply, hamjury. One must be careful not to stretch it too far, of course, and refer to an instep injury as an injury, which could initiate an endless loop of questioning. ("What kind of injury?" "An injury." "Yes, but what kind?" "An injury!")

Fun, no?

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Passenger in toilet

A hotel with a hamstring injury

Guess where I'm staying in Baroda.

Travel, and home

So after 42 days of travelling through Pakistan, I head off to Baroda. How do I feel, at having to travel again? Well, I'm very tired, and I wish I could rest, maybe for a week, maybe a month, maybe longer. I'm lazy. But then, in the handful of days I was at home in Mumbai, I found myself descending into the same slothful habits of old: staying awake till 3am surfing trash or reading magazines or watching TV; playing Hearts through the afternoon in office, trying to make my opponents go 26, 52, 78, 104; lapsing into a jaded, zombielike way of non-thinking.

When I am on the move, it is different: the sheer newness of the landscape around me keeps my mind active, and I am meeting new people all the time, and cannot take anything for granted. Yes, the tea is too sweet, and teabags too messy, and sometimes one has to be social when one wants to be alone, and at other times one feels so alone and there is no one to be social with. Travelling has its own patterns, but (with apologies to Tolstoy) every uninspiring town is at least uninspiring in its own way. Not that Baroda is uninspiring. Not at all.

Off I go then. Ta da.

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

Do not draw my unicorn

Let us say that I believe in the Invisible Pink Unicorn. Deeply. Devoutly. I create invisible pink altars in my house, go on invisible pink pilgrimages, and believe that it is blasphemous to depict the Invisible Pink Unicorn in pictorial form.

Then one day, a newspaper brings out a cartoon depicting the Invisible Pink Unicorn. To my outrage, She is depicted as neither Invisible (obviously) nor Pink. Sacrilige. Instantly I announce rewards for the head of the cartoonist and organise demonstrations in far-off countries where much violence takes place, cars are burnt, property is destroyed. So how do you react? Was the cartoonist wrong in insulting my faith? Is my outrage justified? More importantly, is my behaviour justified?

Now, you'll no doubt say that there is a difference between Invisible Pink Unicorns and that-which-I-shall-not-dare-to-name. No doubt. It is a difference of scale, and that changes our attitude towards it, as brought out by this fine example. But the principles involved remain the same.

When I was in Lahore last week, one of my friends told me about this taxi driver he met who saved for years, took a loan, and combined the loan and the savings to buy a cab. Three weeks after he bought it, a mob burnt it down. Gogol's Overcoat, but so much worse. The poor man was speaking about committing suicide with his family. Now, however insensitive and inflammatory the Danish cartoons may have been, I do not blame them for this man's predicament. Cartoons do not kill people, people do.

Anyway, having said all that, a couple of links. First, the Economist's take on the issue, which I rather agree with. I also agree with what Glenn Reynolds has to say, especially that "[t]hese people [the protesters] are doing more to make Mohammed look bad than any cartoonist ever could." And finally, here's a piece by Flemming Rose, the editor who published those cartoons, on why he did so. At one point, he writes:

Has Jyllands-Posten insulted and disrespected Islam? It certainly didn't intend to. But what does respect mean? When I visit a mosque, I show my respect by taking off my shoes. I follow the customs, just as I do in a church, synagogue or other holy place. But if a believer demands that I, as a nonbeliever, observe his taboos in the public domain, he is not asking for my respect, but for my submission. And that is incompatible with a secular democracy.

Exactly. Worshippers of Invisible Pink Unicorns have no right to demand that submission from others. Nor does anyone else.

Update: Also, do read this old post by MadMan on tolerance.

On naming dogs, and intolerance

I've just received a letter from Naresh Fernandes, editor of that fine magazine, Time Out Mumbai, addressing an issue that I believe is of immense importance to all those of us who believe in individual freedoms. I'm reproducing the letter here, and I endorse especially strongly the last line. If you feel the same way, do take this issue up and spread the word.

Dear Editor

I’d like to call the attention of your readers to a cynical attempt by political workers to inflame religious passions in Mumbai over the last week, harnessing the eager assistance of the authorities to turn the press into the scapegoat. The chain of events went into play with the publication of a report on Feb 19 in the Times of India, detailing the arrest of one of its reporters under 295A of the IPC (deliberately injuring religious sentiments). The article says that the reporter, whom it does not identify, was arrested on the complaint of a local municipal corporator, who claimed to have taken offence at an article written one month ago about pets owned by Bollywood stars. It goes on to state that the arrest was carried out even though the paper had already apologised for details in the article that were later found to be inaccurate; the very details to which the complainant had taken offence.

A subsequent report in Mid-Day on Feb 21 casts more light on the episode. Though the Mid-Day report makes no mention of the arrest of the Times reporter, it says that the actress Manisha Koirala has been provided police protection “after her dog’s name sparked protests among Muslim fundamentalists.” The report says that “members of the community lodged a complaint at Versova police station saying that the dog’s name, Mustafa, was same as that of their spiritual head and had to be withdrawn immediately.”

While the Times management has forbidden the reporter from speaking to the press about the incident, her colleagues have identified her as Meena Iyer, a reporter on the Bollywood beat. They say that she was arrested by the plain-clothes policemen, who appeared at her home at 9 on the morning of Feb 18. At first, they even refused her permission to change out of her night-clothes and they jostled her, her colleagues say.

The episode raises troubling questions. To start with, since the report was published a month before the journalist’s arrest, the police have no real grounds for claming that it had inflamed communal passions. Instead, it is obviously the complainant who is seeking to stoke the fires. It seems baffling that the police would arrest the reporter, instead of the complainant. Considering that the police have in the past failed to act on complaints against hate speeches by such figures as Bal Thackeray, the alacrity with which they arrested Ms Iyer is perplexing.

This is further evidence the Maharashtra government’s willingness to cave in to the demands of fundamentalists, a sentiment that it demonstrated earlier in February by issuing a non-bailable warrant against the editor of the Mumbai Mirror under the same section of the IPC, for printing a photo of an allegedly offensive tattoo. The editor had to obtain anticipatory bail to avoid arrest. In January, the Maharashtra government banned the translation by American academic James Laine of a praise poem, “The Epic of Shivaji”.

Episodes like this greatly compromise our ability to effectively function as journalists, and must be countered with strong condemnation.

Yours faithfully

Naresh Fernandes

Monday, February 20, 2006

Linkaciousness begins soon

When India Uncut doesn't travel, it is largely a filter-and-perspectives blog. In other words, I link to stuff I find interesting and give my two bits. Now that I'm back in India, I'll go back to doing that, but will also try to intersperse it with more personal posts, thus thoroughly indulging myself and boring you.

In the meantime, let me share some links with you. I hardly got time to read anything during my travels, but here are a handful on links that did catch my eye.

1] Rahul Bhatia, whose joyful glow these days is surely caused either by pregnancy or facewash, writes about the loneliness of travel. I read his post at a time when I could so empathise with what he wrote about. The thing is, it's not a loneliness caused by a lack of company, but a deeper, more existential feeling, and one that merely comes to the surface when we are on the road. I'm happy to be back among loved ones, but the feeling is there somewhere, all coiled up and ready to spring loose.

2] Madhu Menon, who left a flourishing career as a tech maestro to start a restaurant, gives us "Tips on making a radical career shift." I love his beef. (No, not what you think.)

3] Sidin Vadukut, who once wrote the funniest post ever, now writes the funniest post ever. Envy comes. (Link via Gaurav.)

4] Chandrahas Choudhury writes a scathing review of Rang De Basanti. He might be shifting to Delhi soon. (The above two sentences are not necessarily related.)

And now, back to my old haunts.

To become a better writer...

.sdrawkcab gnitirw yrt...

(.egaugnal ruoy fo tuo seicnadnuder eht ekat lliw tahT)

New eyes, old eyes

Home always seems different when you return after a long time. I arrived back in Mumbai early Saturday morning after almost two months of travel, of which 42 days were spent in Pakistan, and I looked at everything here with new eyes. Marine Drive seemed sparklingly nice in the evening, all lit up and suchlike, and the city seemed so vibrant, with people on the move everywhere. There were so many options of places to eat at and things to do and magazines to buy and new TV channels to see and so on. And nicest of all, there were so many women everywhere. Why hadn’t I noticed it all these years?

After weeks of excitement, I’d suddenly felt jaded in my last two days in Lahore, no longer excited by the city. Now, after so long away from Mumbai, I am as wide-eyed as a child. How long will this last?

Bye bye love

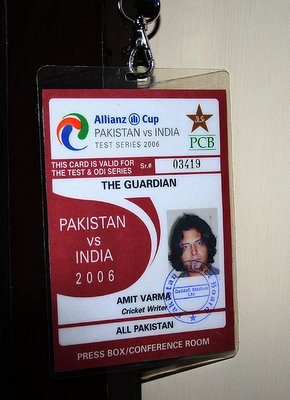

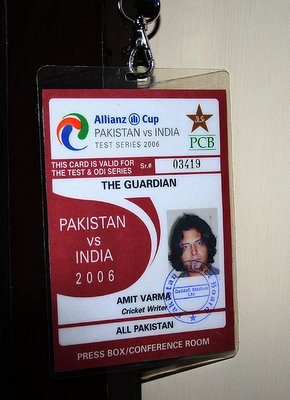

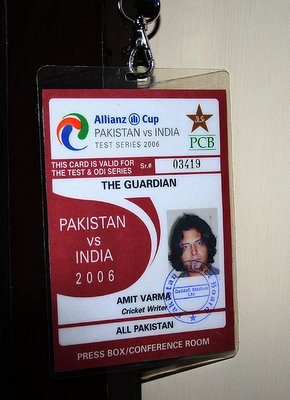

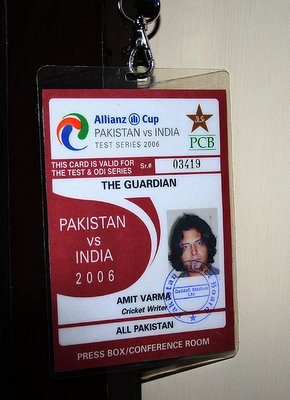

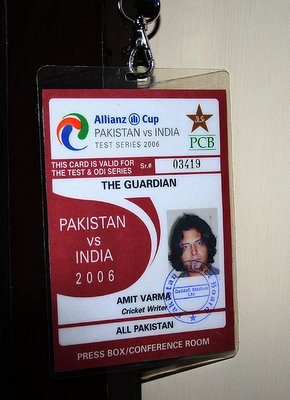

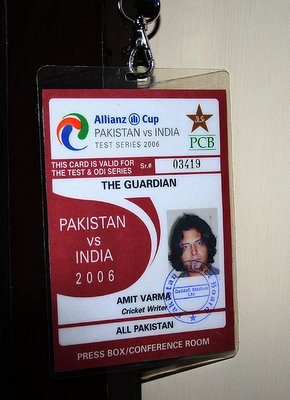

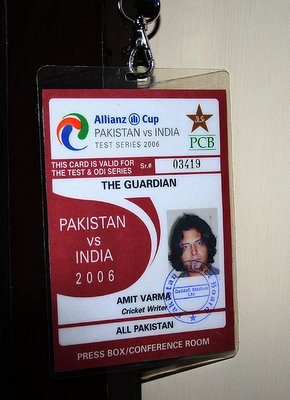

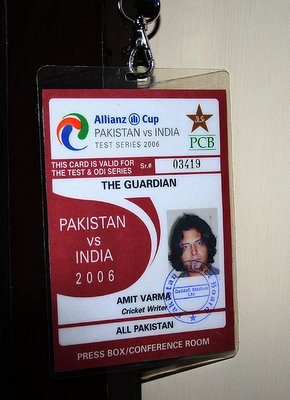

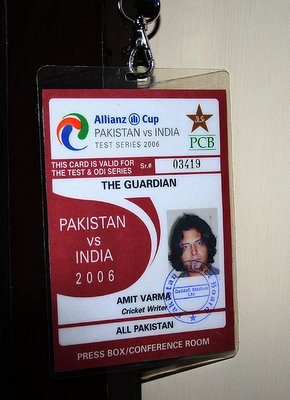

It’s been my most precious possession for the last month-and-a-half, but now I don’t need it any more. Goodbye, media accreditation card.

Note: there are a number of posts about Pakistan for which material was gathered and a start was made, but which I didn’t have the time or energy to finish and publish. As the days go by, I might put up some of those. So you haven’t actually seen the last of my Pakistan trip. Sorry!

Saturday, February 18, 2006

The modern neanderthal...

... wields not a club but a club membership.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Ab Dilli door nahin, and all that

Yes, yes, I haven't blogged in over two days now. I've been alternating bouts of work with bouts of intense tiredness, all the while battling a worm that keeps rebooting my computer. It's frustrating, and I can't wait to get back home. After weeks of excitement, I suddenly feel exhausted, not wanting to work, not wanting to write, not wanting to take photographs, not even wanting to want. That tired.

And the work continues. I'll be flying from Lahore to Delhi tomorrow evening, and getting on the first available flight to Mumbai after that, probably arriving there in the early hours of Saturday. A few hours later, I'll have to be at England's tour game, for which I have to do a report for the Observer. Sigh.

One day when blogging starts paying, I'll do only this and you lot can stop complaining. "He only eats kababs all day and plays with guns," I can hear you think. "What about us, waiting for him to upload his blog? Taking us for granted and all." No, no, no! You're the one I want to pamper and give my undivided attention to, but the world is cruel. Bear with me while I bear with it. And give me a virtual bear hug in the middle of all that bearing, I so need one.

Ok, don't. Bye now. I'll be back later tonight, hopefully, with more conversations with people and suchlike. Yeah, yeah, whatever.

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

A shallow liberalism

I am chatting about Lahore with a new friend, Qurratulain ‘Annie’ Zaman, a sharp 25-year-old journalist who works with the Daily Times here. I’ve been told by a lot of people that Pakistan has become much more liberal in the last few years, that one sees many women in jeans, many women working in Pizza Huts and so on, which one didn’t see five years ago. I ask Annie about that. She says:

The liberalism here is very shallow. Parents will happily allow their daughters to wear tank tops and jeans and go out for parties and so on. But see how they behave when it comes to the cartoon issue. Or when their daughter chooses someone to marry.

They want to feel liberal and westernised, so they allow all these surface displays of so-called liberalism. But deep inside, they haven’t changed.

I nod. I’ve seen such ‘liberalism’ in India as well. And the cappucino is similar too.

Monuments

Late at night after the game at Rawalpindi, a friend and I take off to Daman-e-Koh, the point from which all of Islamabad can be seen. (Islamabad and Rawalpindi are twin cities, by and by.) It’s a remarkable view from there. Islamabad is a city that was planned from scratch, like Chandigarh, so all the lights below us are set out in neat geometrical formations, as the haphazard and organic growth that takes place in other cities – and that I love about cities, in fact – has not taken place here. But the most stunning aspect of the view is the Shah Faisal Mosque.

From on top, one realised how big it is. It is huge. Later, we drive down to the mosque itself, and it is just as impressive when one is close to it. Awe comes.

One of the ways in which religion has inspired awe in its followers through the ages is through the grandeur of its monuments. Architecture on such a scale is humbling. Being an atheist, of course, I can see through the façade: good tactics, I think to myself, but I don’t buy the message. I am less interested in 'God' than the people and the world we live in, and the monuments I would respect most are the ones that are good for them.

And there are two monuments, not of stone or cement but of human actions, that I’d love to see being built in the subcontinent: an open society and a free economy. To guarantee individual freedoms to everyone in the true sense of classical liberalism would be, well, what I’d call divine.

I’m not holding my breath.

Where is Denmark?

I am chatting with Zafar Abbas, the head of BBC in Pakistan, and I ask him about the cartoon controversy, and the demonstrations against it.

“Most of the people demonstrating against the cartoons haven’t even seen them,” he says. “In fact, if you ask them where Denmark is, most of them won’t know.”

“So why bother to protest then?” I ask. “Who benefits from these protests?”

“The religious groups which organise these protests do so just to register their position,” he says. “In future, if they’re ever asked about this issue, they can point to the protests and say, ‘See, we took a stand.’”

“And is that the only way they know to register their protest?”

“Yes.”

What responsibility does

The further away you are from power, the more irresponsible you can be, because the positions you hold have no consequences that impact you directly. We see this mismatch between power and responsibility in the Left parties on India. At the centre they enjoy a veto without actually being part of the government, and they take anti-reform positions that harm the country. In Bengal, though, they are the ruling party, and are setting a benchmark for other reforming states with their opening up of the economy. When they are directly responsible for the well-being of their people, they act more responsibly.

I was given two further examples of this phenomenon by Zafar Abbas, the head of BBC in Pakistan. Zafar is based in Islamabad, and has faced all kinds of intimidation in his 15 years with the BBC: his office in Islamabad was burnt down once by a religious group, and he was beaten up; on another occasion, his house in Karachi was stormed and he ended up in hospital. Indian journalists have it easy compared to their counterparts in Pakistan.

I had an enlightening chat about Pakistan with Zafar, in the course of which he gave me, though not in that context, two further examples of how being in power changes attitudes. One, he said, now that the religious parties have formed the government in the North-West Frontier Province, otherwise a hotbed of extremism, they act far more responsibly there than they used to. Whether it is regarding the protests against the US that took place last month, or the uproar over those Danish cartoons, they’ve been more muted than you’d otherwise expect.

Two, there is the military. Now that the military actually runs the government, Zafar tells me, and are directly responsible for the well-being of the country, their policies are more responsible than what they’d otherwise suggest. The buck, they know, stops with them.

And because of all this, I’m not as pessimistic about Hamas coming to power in Palestine as so many others are. Let’s wait and see how they behave now.

Monday, February 13, 2006

Peace in South Asia

Thank for not you smoking

Saturday, February 11, 2006

Product of the times

Friday, February 10, 2006

Apollo Bunder

What is more poignant than being a stranger in your own land? Via Murali, I met up with Jimmy M Framjee and his daughter, Rukhsana, who are, they say, the only Parsis in Islamabad. Jimmy used to own a thriving business selling liquor, which collapsed once prohibition was imposed. Rukhsana now has a small business selling soft drinks from her house, but they are essentially living on the past, and in the past.

Jimmy is from Navshera near Peshawar, and he used to own a shop – M Framjee and Sons – that sold liquor there. When it was outlawed in NWFP, he shifted the business to Islamabad and settled here. But then came the Zia years, and prohibition wiped out his shop, which was based in Islamabad’s popular Super Market. “I couldn’t afford to pay the rent,” Jimmy said, “if I couldn’t sell liquor. So I had to shut it down.”

“What did you do then?” I ask.

“What could I do?” he asks back. “I was growing older.” He pauses. His eyes are moist, and I change the subject. I ask Rukhsana about Mumbai. Rather, for her, Bombay.

Rukhsana bubbles with energy, and seems particularly excited that guests have come, and she can speak to them about shared places. She loves Bombay, and has many relatives and friends there. She starts speaking about it, and every sentence seems to have two exclamations marks at the end. Her voice dances when she goes over the names of places, and her eyes light up. I can’t remember the exact words, but I remember some of the places she mentions, and the sentiments.

You know, we travelled once to Bombay by train in a dining car … Such lovely chicken curry … I love fish …And what local trains … Andar ka jhoka, andar, baahar ka jhoka tho bahar … Once I was travelling from Churchgate to Dadar, and I couldn’t get out! My purse got stuck! All the ladies said, leave your purse, but I said no, why should I leave my purse? I got down in Andheri!

How I loved travelling in the BEST buses! Double decker, single decker, sab kiya re!

And Delhi! How I loved Chandi Chowk! … Once I went to that underground market near Janpath, kya naam hai, yes, Palika Bazaar! How much time we spent inside, every shop I visited. We went in at 12 in the afternoon, and when we came out, it was dark! Chhe baj gaya tha! … I saw a pani puri man and called him and said idhar aa, pani puri khila! …

And once we went to Delhi and took a Rajdhani to Bombay. What a train!

Rukhsana then starts talking about Bombay again, all the places she goes to, and her friends in Parsi Colony. And at one point, Jimmy, his eyes still moist, speaks up.

“Apollo Bunder,” he says. “I used to go to Apollo Bunder.”

Rukhsana beams at me. “Arre, why are you talking about all this to me, I feel like I’m in Bombay again, I feel like I’m sitting in Bombay.” The room is full of memories, and she is happy. And yet, though she smiles, I sense a sadness as well. The memories are fresh now, and yet I can imagine how far away the past must feel sometimes. As if it’s another country.

The press and its freedom

I am sitting with KJM Varma, the PTI correspondent in Islamabad, and Murali, the Hindu correspondent. We’re discussing how free the press is in Pakistan – indeed, I find far more articles critical of the Pakistan government here than in India – when KJM tells me that the press isn’t doing enough with its freedom. He says:

You’ll find plenty of Op-Eds and editorials critical of the establishment, but that attitude doesn’t reflect in the news pages. They are still full of the same old thing. Where is the investigative journalism, the sting operations? Pakistan needs a Tehelka.

Considering what a democratically elected government did to Tarun Tejpal and his team during the Vajpayee years, I shudder to think what General Musharraf’s government in Pakistan would do if similar defence ghotalas were exposed here. It would be interesting to find out, wouldn’t it?

9/11 and Pakistan’s economy

The world changed on September 11, 2001, and for Pakistan, it changed for the better. Akbar Zaidi, an economist I met in Karachi, told me that the upturn in Pakistan’s economy was entirely due to foreign aid. He explained that in the context of why Pakistan’s economy seemed to do better under military rulers: not because there something inherently sound about military rule, but because of happenstance: the periods of military rule happened to coincide with Pakistan’s emergence as a strategic hub for the USA in South Asia. General Zia-ul-Haq benefited from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and General Pervez Musharraf gained from 9/11.

The world changed on September 11, 2001, and for Pakistan, it changed for the better. Akbar Zaidi, an economist I met in Karachi, told me that the upturn in Pakistan’s economy was entirely due to foreign aid. He explained that in the context of why Pakistan’s economy seemed to do better under military rulers: not because there something inherently sound about military rule, but because of happenstance: the periods of military rule happened to coincide with Pakistan’s emergence as a strategic hub for the USA in South Asia. General Zia-ul-Haq benefited from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and General Pervez Musharraf gained from 9/11.

As Pakistan became a frontline state in the War against Terror, massive US Aid flowed in, as external debts were restructured in favourable terms and the Americans took an active interest in keeping Pakistan afloat. Dr Farrukh Saleem, an economist, wrote in a recent column in The News on Sunday:

[T]he US Department of Defence has been depositing a cool $100 million a month into our treasury for the last four years. The US forgave $3 billion worth of bilateral debt, and then convinced the Paris Club lender nations to reschedule a large portion of our $38 billion bilateral debt on easy terms. Add it all up -- and thank Osama -- for the total bonanza is going to be a colossal $40 billion.

Thank Osama indeed. Murali, my new friend in Islamabad, tells me that some Pakistani journalists would refer to Al Qaeda as Al Faeda after 9/11, such was the benefit to Pakistan. We were chatting about Peshawar, and Murali said, “There are journalists in Peshawar who became crorepatis after 9/11. They would charge 300 dollars a day to act as local guides for foreign journalists.”

“You mean 9/11 spawned a support industry of its own?” I asked.

“Not just 9/11, but also the earthquake,” he said. That took my mind back to a gentleman from Islamabad whom I’d met in Karachi, who rented his posh SUV out, at an exorbitant rate, to foreign aid workers to visit the earthquake-affected areas in.

“The price of land also shot up,” Murali tells me. “Non-resident Pakistanis got worried about investing abroad, and felt safer investing in Pakistan. Also, a lot of people felt that they’d rather keep their money in real estate than in banks.

“In fact, if 9/11 had not happened, the dollar would have been 80 or 90 [Pakistani] rupees instead of what it is now. [Between 55 to 59, depending on the source.]”

9/11 also gave Pervez Musharraf respectability, of course, and it helped in legitimising his rule. But I’ll write more on Musharraf later.

Kicking schoolbags

On my first morning in Islamabad I met one of the most interesting – and nicest – people I’ve met in Indian journalism: B Muralidhar Reddy. Murali is the Pakistan correspondent for the Hindu and Frontline, and has been in Islamabad for around five years now. I called him up and asked to meet him because I thought that having lived here for so long, he’d be full of interesting insights into Pakistan. He was, and to my surprise and delight, he also turned out to be a regular reader of India Uncut. That makes five, unless I’m not allowed to count myself.

I can’t possibly reproduce the long and interesting chat I had with him, but there’s one bit which stood out in my mind, and seemed blogworthy. We were speaking about how the visa restrictions on Indians in Pakistan are not extraordinary when we consider that the Indian government places similar restrictions on Pakistanis, and he said:

You know, Amit, if something happens to me here, and I report it to Delhi, the Indian government makes sure that exactly the same thing happens to my Pakistani counterpart out there. If I tell them that my house has been burgled, they will presume that it’s the work of the Pakistani government, and exactly the same kind of burglary, in exactly the same manner, will take place in my counterpart’s house in Delhi. I have seen this happening time and again.

That is why we [Murali and KJM Varma, the PTI correspondent here] have decided that no matter what happens to us, we will not report it to our government.

Needless to say, I have no personal complaint: the journalists travelling along with the cricket tour have been treated exceptionally well, with no need of police reporting etc. But other visitors from India often go through hell to get here and have all kinds of restrictions placed on them, all mirroring what the Indian government does to Pakistani visitors. It’s remarkable how petty and immature the two establishments are: It’s like two 12-year-old boys messing with each other's schoolbags during a break. One hurls the other’s schoolbag on the ground, the other reciprocates. Kick the bag. Reciprocate. Spit on it. Reciprocate.

In the end who suffers? The schoolbags do. Forgive me for the shoddy metaphor, but who are those schoolbags?

The people of India and Pakistan.

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Solitaire in a moving car

Guns, guns, guns

One of the fundamental rules of human bevaviour that governments don’t get: if you ban something, you don’t end it, you just drive it underground. If there is demand, supply will come. Booze is freely available all across Pakistan, and drugs much more so than anywhere I’ve seen. And in Peshawar and outside, along the roads that lead to the Khyber Pass and on it, guns are openly available, from Kalashnikovs to German automatics. My friends and I, from peacable India, gawked at these glimpses of frontier life, tip toed into one such shop, and checked out said weapons. I caressed nozzles, teased triggers, cradled butts. I almost came – thank god the guns didn’t.

Here are some pics, including one of me (with spectacles) and the infamous Faisal Shariff, trying our best to look macho but failing miserably despite the guns. The girls prefer sensitive men, I’m told, so maybe we’ll try for that slot.

(Pic of me and Faisal by Ramesh Athani.)

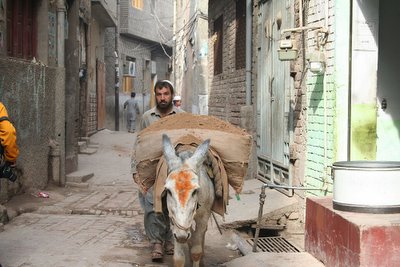

Down the Khyber Pass

There is a sense of romance about the Khyber Pass, and a sense of foreboding. This was the trade route between what one today calls South Asia and the rest of the world; this was also the road the invaders and marauders took to get here. All that is in the past, of course, but the present holds as much mystery. The route today is surrounded by tribal areas of the North-West Frontier Province where Pakistan’s government has no control, where loya jirgahs, and not Pakistan’s courts, administer the law. There are intricate networks of associations within and between tribes, all of which can be daunting for an outsider, one wrong step by whom can lead to trouble.

Outsiders need a permit to go here, but some journalist friends and I took off nevertheless in a minibus, picking up a friendly local guard along the way to show us the way. The landscape was rugged – like Leh, said one of my companions – and the houses like nothing we’d seen. Jamrud was full of small fortress-like houses, belonging to the Afridi tribe – stark walls with small openings, as if for peeping out or firing from. The landscapes and the buildings together say a lot about a place, though merely riding through the areas doesn’t equip us to interpret any but the most superficial parts of it.

We drove through Jamrud, Landi Khana, Ali Masjid, Michni and Landi Kotal. We stopped at times, to just look and take pictures that will later seem to be of just any mountain range. Sometimes, confronted with history, we try so hard to feel special, don’t we? We stop at a place where the view is as it would be from Manali, but that seems a mundane thing to think. Heck, this is the Khyber Pass! We’re on the Khyber Pass! You express wonder, trying hard to feel it, and every turn of the road feels special.

And then you stop at a place and your guide points something in the distance and tells you what you’re looking at, and you do feel that chill up your spine.

Afghanistan.

In the last picture below, the one with the guard in it, see the mountain in the distance that has “2” written on it. Beyond that is Afghanistan. But all that is just lines on maps. Where we stand, the road we have come through, is more Afghanistan than Pakistan. It makes me wonder about constructs like ‘Pakistan’ and ‘Afghanistan’ and so on, artifically put together, as if people and cultures were lego blocks. They cannot envelop what they are supposed to contain, and I haven’t, through all this trip, got a sense of what Pakistanness, or Pakistaniyat, or whetever you call it, really is. I’ve got a sense of Lahore and Punjab and Sindh and Peshawar, but not Pakistan.

And sometimes back home I don’t get a sense of India either.

Jaziya

I’m sure you know how Islam is. You can do one of three things in the tribal agencies. One, you pay jaziya. Two, you embrace Islam. Three, you prepare to die.

We pay jaziya.

That’s Taranjit Singh, a Sikh from Peshawar telling me about how the Sikhs of Peshawar get by. Jaziya is a religious tax that some Muslim kings – most infamously the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb – used to levy on Non-Muslim subject. I’d always thought the practice had died out a couple of centuries ago, but large parts of the North-West Frontier Province, where I am right now, are stuck in an old time warp. Although it falls in Pakistan, Pakistan’s government has no formal control over much of it, especially in the Khyber Agencies, where different tribes (or agencies) control different areas.

“All law is administered by the loya jirgah,” Taranjit tells me. “If we Sikhs want to survive in those mountaneous areas, we have to have a tribal represent us there. We pay him certain money, and he looks after our interests. It is like having a lawyer.”

But it isn’t like a special-interest group hiring a lobbyist, because Taranjit uses the word ‘jaziya’ repeatedly. It’s about religion.

* * *

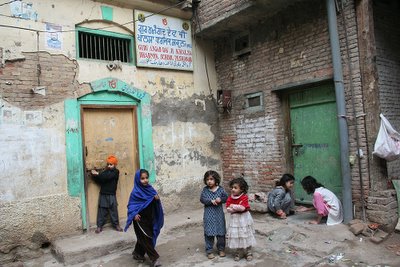

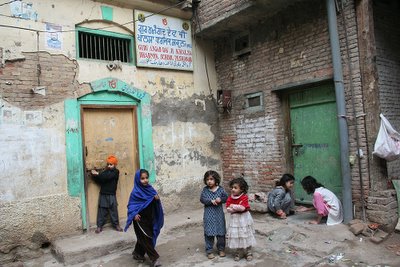

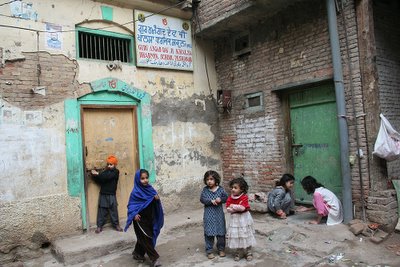

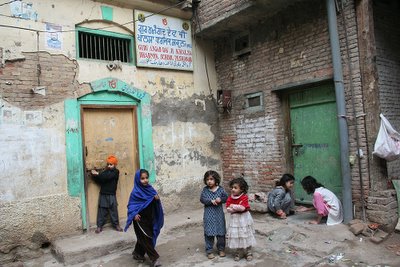

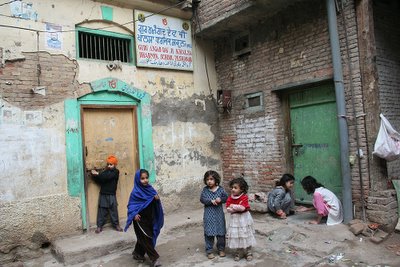

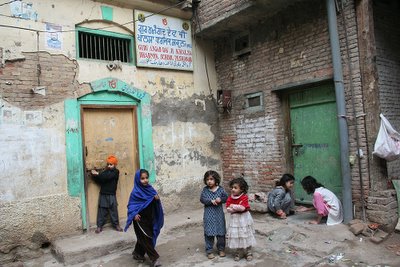

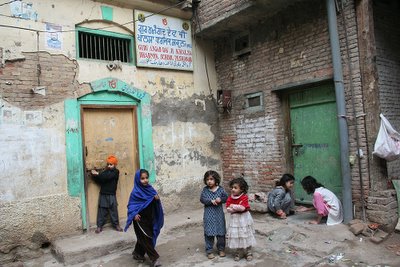

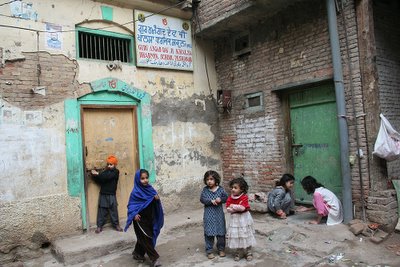

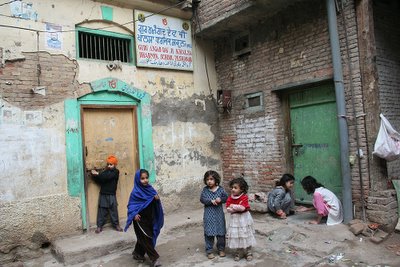

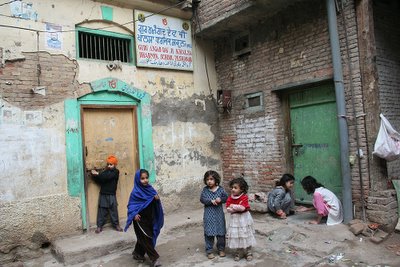

We are sitting in the Gurudwara Bhai Joga Singh, in the Mohalla Jogan Shah Dabgari in Peshawar. We have got here by winding our way through a series of lanes and bylanes, and would have trouble getting out of here without a guide.

Taranjit tells us about how this gurudwara came to be. “It was founded by Hari Singh Nalwah,” he says, “the general of Ranjit Singh’s army. [The Sikh empire once extended to Peshawar.] Hari Singh Nalwah was said to weigh 250 kgs. He was the strongest man in the universe. Once, he slapped a man and his head got dislocated from his shoulder. His chest was equal to that of seven people.”

I am tempted to ask if he could fly when Taranjit continues: “No horse could carry his weight. Then one day a horse was found from Baluchistan that could carry his weight.”

“Would you happen to know the name of that horse?” I ask.

Taranjit looks at me oddly. “Horses don’t have names,” he says.

“Anyway,” he continues, “Hari Singh Nalwah built around 2500 gurudwaras in Punjab, under the patronage of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.”

“How many of these exist today?”

“Maybe about 800,” he says. I find later that this figure is hearsay, that it could be less, it could be more. Across the country, in fact, there are ex-gurudwaras that have been converted into schools, jails, homes and suchlike. The religion was almost wiped out when the partition of India took place.

“All the Sikhs either shifted to India or went into the mountains,” says Taranjit. “Only recently have they started coming down from the mountains.” Peshawar has more Sikhs than any other city in Pakistan. Pushto is the mother tongue of most of them.

Taranjit introduces us to Sardar Shona Singh, the pramukh of the gurudwara. “This gurudwara was shut down in 1947,” Sardar Shona Singh says. “Then, in 1980, the Pakistan government gave us permission to start it again. It took us three days just to clean this place up.”

Pakistan’s government, they assure us, is quite “supportable” of the Sikhs. But then, just as we are beginning to think about how the country is slowly becoming more liberal, he tells us about Jaziya.

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

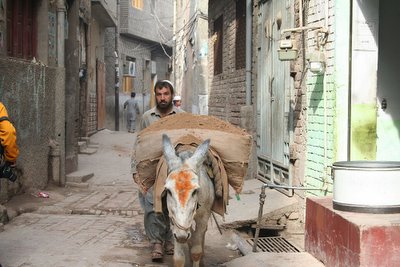

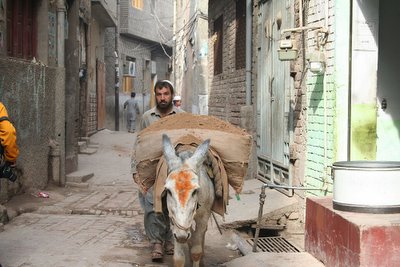

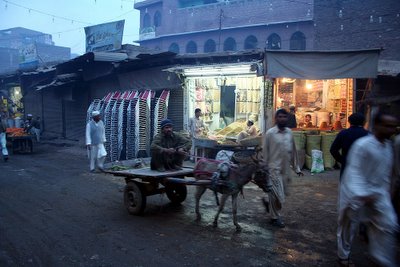

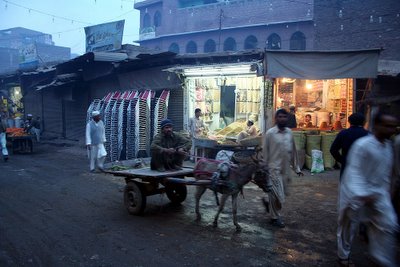

Namak Mandi

When in Peshawar, have the charsi tikka at the Namak Mandi. Nyo, nyo, nyo, the charsi tikka doesn't actually have any charas in it, but is called that because its pioneer here was a charsi. And no namak (salt) seems to be sold on its own in Namak Mandi, which was once called Mewa Mandi but got itself a name-change when namak began to outsell mewas. Today, however, the place is more famous for its meat.

It's vegetarian hell. Carcasses of dead animals are strung up everywhere, and you can take your pick. Your choice will then be prepared for you, roasted on a cart on the street without any masala except salt. The meat, fresh and with a texture that is a remarkable mix of meltacity and chewiness, is eminently mmmable.

Local friends tell me of people who have up to 10 kgs of meat in one sitting. When it tastes so good, I'm not surprised. How to stop?

To provide an interesting contrast, there is also a shop opposite selling dry fruits. The gentleman who owns it looks upon the meat-eating revelry across the road rather sternly, perhaps wondering how so many otherwise sensible people prefer flesh to raisins. Our species, of course, is a slave to flesh, in more ways than just the culinary ones.

Enough. Pictures come:

Peshawar to Calcutta

Just off the corner of Namak Mandi, I get chatting with a gentleman named Mohammad Anwar, who makes and duplicates keys. As soon as Mr Anwar learns that I'm from India, he asks , "Have you heard of Sher Shah Suri?"

Just off the corner of Namak Mandi, I get chatting with a gentleman named Mohammad Anwar, who makes and duplicates keys. As soon as Mr Anwar learns that I'm from India, he asks , "Have you heard of Sher Shah Suri?"

"Er, yes," I reply.

"Well then, you must know that he built the Grand Trunk Road, which connects Peshawar to Calcutta. Now, that Grand Trunk Road, to me, is more of a truth than India and Pakistan."

He nods wisely here. I nod as well.

(The GT Road actually goes beyond both Peshawar and Calcutta, but you get the point.)

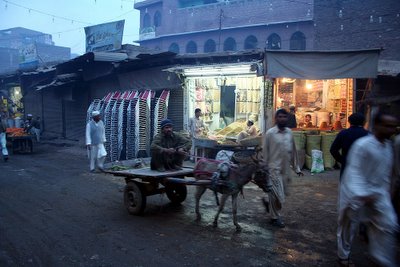

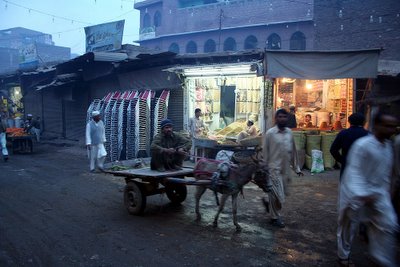

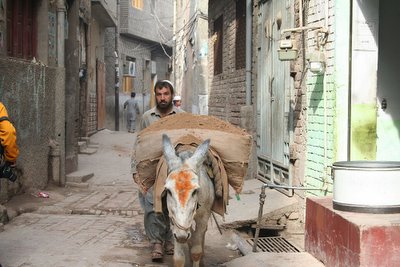

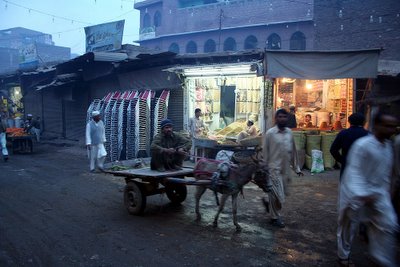

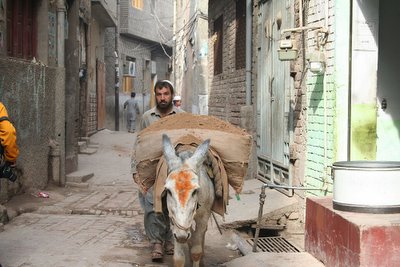

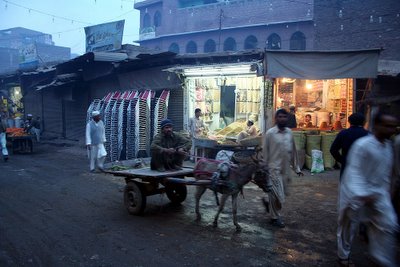

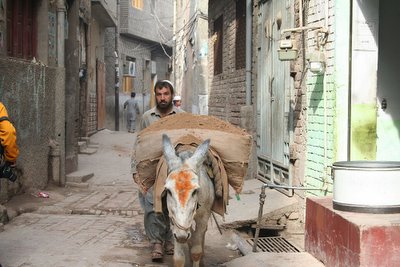

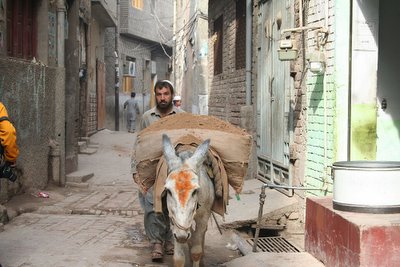

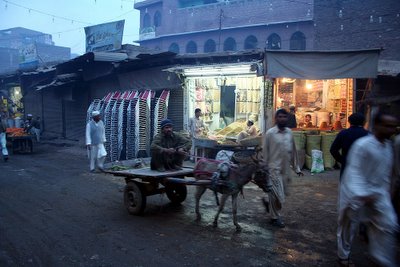

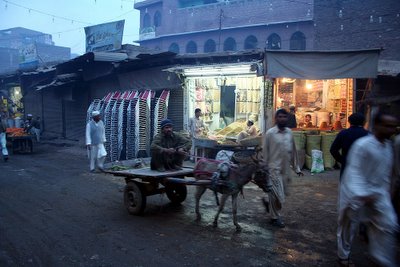

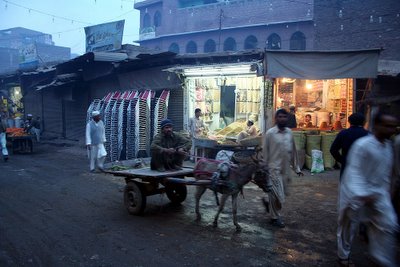

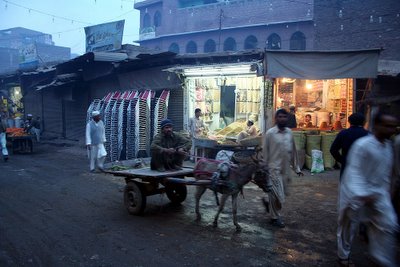

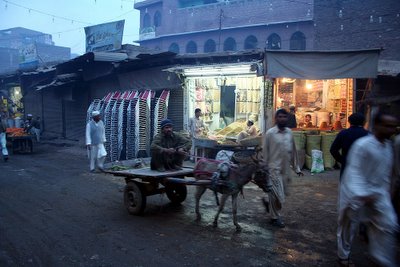

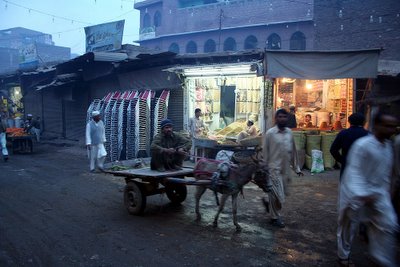

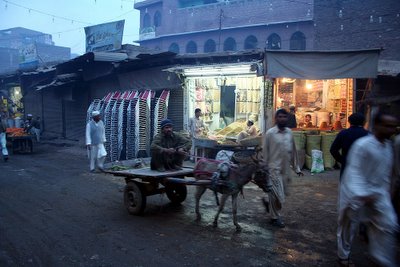

Twilight in the street of storytellers

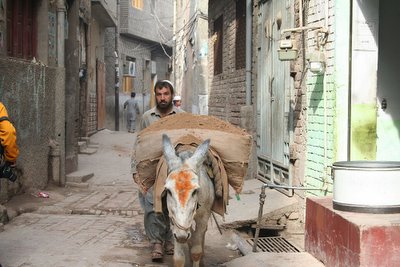

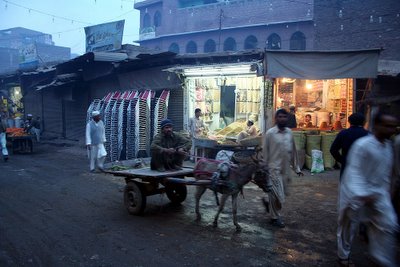

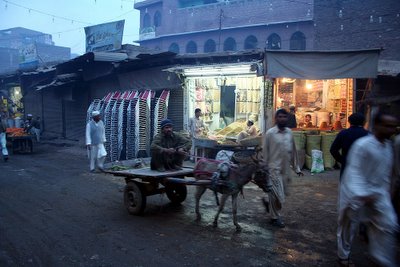

It’s evening when we set out for Peshawar’s famous Kissa Khawani – the street of storytellers. It’s that time of the day when the stars are in purgatory, slowly waiting as daylight fades. We walk through a lane full of shops selling dry fruits, and in one of them my friend chooses kishmish from Iran over kishmish from Afghanistan. We take another lane, in which all kinds of colourful baubles and trinkets hang. The day changes. It’s peaceful.

The lights in the shops have started to come on, but the streetlights remain off. We reach a vegetable market, a bit of a curiosity in this land of meat-eaters. Hawkers sit under suspended polythene sheets that act as the boundary between daylight and nightlight.

Then daylight’s gone, and so are we.

One of the characteristics of Amitava Kumar's writing is that he doesn't flinch from the personal, and you'd think that he would make an excellent blogger. Well, he does. The writer of books such as "Passport Photos ," "Bombay-London-New York

," "Bombay-London-New York " and "Husband of a Fanatic

" and "Husband of a Fanatic " has started blogging, and India Uncut welcomes him to the party.

" has started blogging, and India Uncut welcomes him to the party.

And what better way to check out his blog that to begin with an open letter, "Lalu Yadav to George Bush."

And what better way to check out his blog that to begin with an open letter, "Lalu Yadav to George Bush."

Crash

Despite buying around 50 DVDs during my travels through Pakistan, I hadn't actually seen a single film this year until yesterday, when I finally returned to Mumbai from Baroda. My DVD player is misbehaving these days, and we went off to Fame Malad to watch "Crash." We could hardly have made a better choice.

"Crash," directed by Paul Haggis, is an ensemble film, with various interweaving storylines, much like Robert Altman's "Nashville " (which I loved) and "Short Cuts

" (which I loved) and "Short Cuts " (which didn't live up to my expectations from reading the stories and seeing Altman's previous work), but crisper, tauter, and more packed with emotion. There are some remarkable set pieces in the film, and continuous build-ups and releases of dramatic tension. There isn't a wasted moment through it all, and characters are established with both economy and depth, sparking both recognition and introspection. The cinematography and the background score are wonderful, expressive but unindulgent.

" (which didn't live up to my expectations from reading the stories and seeing Altman's previous work), but crisper, tauter, and more packed with emotion. There are some remarkable set pieces in the film, and continuous build-ups and releases of dramatic tension. There isn't a wasted moment through it all, and characters are established with both economy and depth, sparking both recognition and introspection. The cinematography and the background score are wonderful, expressive but unindulgent.

The theme of the film is how we tend to stay cocooned in our own little worlds, and are suspicious of those outside it. All the characters in this film crash through those barriers, and are forced to re-evaluate themselves and the worlds they inhabit. "Crash" has been praised as being an acute picture of race in America, but like all great films, it speaks to everyone, and to the condition we all share.

I won't elaborate much on plot -- this is not meant to be a review -- but do go out and watch the film . It's outstanding.

. It's outstanding.

PS: Here are reviews of "Crash" by David Denby and Roger Ebert.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

"Crash," directed by Paul Haggis, is an ensemble film, with various interweaving storylines, much like Robert Altman's "Nashville

The theme of the film is how we tend to stay cocooned in our own little worlds, and are suspicious of those outside it. All the characters in this film crash through those barriers, and are forced to re-evaluate themselves and the worlds they inhabit. "Crash" has been praised as being an acute picture of race in America, but like all great films, it speaks to everyone, and to the condition we all share.

I won't elaborate much on plot -- this is not meant to be a review -- but do go out and watch the film

PS: Here are reviews of "Crash" by David Denby and Roger Ebert.

On open-air press boxes

They're great because they give you a sense of how the crowd's feeling and what the weather is like and you get a sense of being part of the action. An AC press box insulates you from all that, and you're halfway to not being at the ground. On the other hand...

... On the other hand, it's bloody hot.

Friday, February 24, 2006

... On the other hand, it's bloody hot.

The mall and the mandi

Going around Alkapuri in Baroda last evening, I passed several malls, and all of them looked the same. There was, at a lower level than the main road, a courtyard surrounded by stores on either sides, leading to a large U-shaped apartment complex at the end, with offices and stores on multiple levels. The courtyard had motorcycle parking in the middle, walking space along it, and two to four levels of shops on either side. It was like a design template, and many malls on that road, all of which would begin shutting down between 8.30 and 9 pm, looked just like that. Here's a pic of one such:

Two nights back, I had dinner with some friends in some another part of Baroda, and their house was in an apartment complex opposite a sabzi mandi (vegetable market). Although their flat faced the other direction, a fair bit of noise from the market filtered into their apartment. It sounded like people rioting. Given what this city has been through in the last few years, it was a disconcerting sound.

The adventures of Ponty Manesar

An even bigger question than “How does one entertain oneself in small towns?” is “How does one wake up early in small towns?” Yesterday, the first day of the tour game between England and the Board President’s XI, I had trouble rousing myself out of bed, as did my room-mate, young Jamie Alter from Cricinfo. What finally woke us up was a series of fine adventures we concocted around Ponty Manesar – as we call this feller.

The previous day young Jamie had watched Ponty drop a few catches in the nets, and Ponty had seemed to be rather hapless, the kind of young man who gets ragged by his team-mates and suchlike. Plus, he’s a surd. So we imagined a number of situations in which Ponty finds himself, which are all very PJ-like, but we rather enjoyed some of them, so why not blog them? I’d like to emphasize that neither of us have met Ponty, and all these stories are entirely fictional. Also, if Monty is reading this, apologies! Here we go:

* * * *

Ponty Manesar shares a room with Shaun Udal, one of his spin rivals in the England team. Udal notes that Ponty is not too good at taking catches. So he decides to tire his rival out the night before a game. He buys a crazy ball, and says to Ponty, “Catch, Ponty!” Then he throws the crazy ball at a wall, and as it bounces from wall to wall, young Ponty runs around madly trying to catch it, arms and legs flailing here and there. Every once in a while, Udal throws another crazy ball at a wall and shouts, “catch, Ponty!”

* * *

Ponty is appealing in his sleep (verb, not adjective) when Udal, disturbed by the noise, shakes him awake and says “Ponty, keep it down!” Then he turns and goes back to sleep.

Poor Ponty wonders what it is that Udal wants him to keep down. He looks all around him and, not finding anything else, puts the phone on the floor.

* * *

A few minutes later, an idea strikes Ponty: Udal is his rival for a place in the side, and here’s Ponty’s chance to make him ill so he can’t play. Ponty gets up and puts on thermal underwear. Then he wears his thickest shirt, and a pair of corduroy trousers. Then he puts on a sweater, a jacket and a monkey cap over his patka. Then he lowers the AC temperature as far as it will go and gets into bed, and waits for Udal to fall ill.

After five minutes Ponty is asleep. Udal wakes up and feels a bit cold. He turns off the AC. Then he looks at Ponty, sees the way he’s dressed, shakes his head sadly, and goes to sleep.

* * *

Udal is chatting with Ponty in the morning. “Plunkett has an inferiority complex,” he says, “and Vaughany has a superiority complex.”

“That’s nothing,” says Ponty. “My uncle in Ludhiana has a shopping complex.”

* * *

That morning when young Jamie and I are on our way to the stadium, we see Ponty on a stationary bicycle in the middle of the highway. We stop to say hello.

“Arre, stadium kahan hai?” he asks.

We point the way.

“Thanks,” he says, and starts cycling faster than ever.

* * * *

Somebody asks Ponty what his favourite TV show is. He says:

“Ponty Mython.”

* * *

Michael Vaughan decides that as this is a practice game, he wants to see both Udal and Ponty in action at the same time. He decides that they will bowl at the same time from the same end. He explains this to them.

“Shaun, you will bowl over the wicket,” he says, “and you, Ponty…”

“I know, I know,” says Ponty. “I will bowl under the wicket.”

* * *

Ponty, when tying his patka in the morning, accidently picks up a pink saree that happens to be lying around in the room, and uses that for his patka. Later in the day, he is fielding at midwicket, and a ball is hit past him towards the boundary. As he chases it, his patka starts unravelling. As he runs from midwicket to deep midwicket, a train of pink chiffon forms behind him.

* * *

Jamie and I are at a shopping complex in Alkapuri in Baroda when we come across a shop called Pinky’s. Instantly we call the Taj Hotel where Ponty is staying and give them a PR idea. The next morning, they conduct a special presentation for Ponty. They are going to unveil a painting for him, they say.

Duncan Fletcher goes backstage before the show to see what the painting is. They unveil it. It shows Ponty in a pink patka, and is titled, Ponty’s Pink Patka. “It alliterates, sir,” the PR manager explains. “A blogger gave us this idea.”

“But his name isn’t Ponty,” Fletcher points out. “It’s Monty.”

The hotel guys scratch their heads and call the painter. He changes the painting. They call it Monty’s Mink Matka, and also present him with a matka made of mink.

* * * *

Young Jamie, Ponty and I are strolling in the evening at Alkapuri when we see a store called “Aradhana Dresses.” Ponty gets very excited and rushes in. He looks here and there, almost jumping around. The storekeeper asks him what he wants.

“The sign outside said Aradhana Dresses,” Ponty says. “I’d really like to see her when she dresses. Please please please.”

* * *

Ponty enters a stationery shop with us and refuses to move.

* * *

Ponty drops us off to our hotel, and in the lobby, he sees a sign that says “Ladies.” Instantly he rushes in there. A manager rushes behind him and asks him what he wants.

“Ladies,” he says, sheepishly.

* * *

The next morning, because the Englishmen are a long way from home and some of them have started bothering Ponty, who at least has long hair, the families of the players join them. The team bus goes to the airport to get them, and brings them to the team hotel, where the team is waiting.

One by one the players’ wives and girlfriends emerge. Finally, at the end, emerges Ponty’s aunt from Patiala. (“Harvinder aunty!” he exclaims.) Then his uncle from Ludhiana. (“Harvinder uncle!”) Then his 16 cousins from Amritsar and his four grandparents from Bhatinda. And so on.

When all 29 have emerged from the bus, Ponty turns to Udal and says, “Mate, sorry, I forgot to make hotel bookings for them, they’ll be staying in our room.”

* * *

Ponty becomes a star in India, and gets an offer to play the lead role in a porn film. He accepts, rather excited at the idea.

“And what would you like to call yourself?” the director asks him. He replies:

“Pondy Manesar.”

I aspire to be a dental plosive...

... and wish to meet fricatives, with whom I can produce affricates.

You can read all about me here.

(Link via email from MadMan.)

He gave me all his soap

Priyanka Joseph points to an article where a Korean comfort woman talks about a kamikaze pilot who "repeatedly raped her" and then fell in love with her and made up a song that helped her survive. Who felt the greater sadness, I wonder: the man who knew he was going to die, or the woman who knew she would have to live like this?

Thursday, February 23, 2006

The secret behind Mallu names

For the sake of justice

Jessica Lal didn't get it. But you can help ensure that Manjunath Shanmugam does. Click here for details.

The charms of Neenjari

I'm at the IPCL ground in Baroda, where England is playing the Board President's XI, and we were told in the morning that Michael Vaughan would not be playing the game because of a knee injury. Instantly the thought came to mind that 'knee injury' doesn't quite glide off the tongue, requiring an unpleasantly forced pause between 'knee' and 'injury'. In fact, any combination of two words where the first ends with a vowel and the second starts with one faces this problem. Why not combine those words then, eliminating one of the vowels?

Thus, 'knee injury' would become 'neenjari', 'toe injury' would become 'tonjari' and so on. You could even use this trick for phrases that involve a consonant, as long as the neologism doesn't confuse. For example, what else could an earjury be but an ear injury. In the case of long words, entire syllables could be removed, as a hamstring injury could become, simply, hamjury. One must be careful not to stretch it too far, of course, and refer to an instep injury as an injury, which could initiate an endless loop of questioning. ("What kind of injury?" "An injury." "Yes, but what kind?" "An injury!")

Fun, no?

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Passenger in toilet

A hotel with a hamstring injury

Guess where I'm staying in Baroda.

Travel, and home

So after 42 days of travelling through Pakistan, I head off to Baroda. How do I feel, at having to travel again? Well, I'm very tired, and I wish I could rest, maybe for a week, maybe a month, maybe longer. I'm lazy. But then, in the handful of days I was at home in Mumbai, I found myself descending into the same slothful habits of old: staying awake till 3am surfing trash or reading magazines or watching TV; playing Hearts through the afternoon in office, trying to make my opponents go 26, 52, 78, 104; lapsing into a jaded, zombielike way of non-thinking.

When I am on the move, it is different: the sheer newness of the landscape around me keeps my mind active, and I am meeting new people all the time, and cannot take anything for granted. Yes, the tea is too sweet, and teabags too messy, and sometimes one has to be social when one wants to be alone, and at other times one feels so alone and there is no one to be social with. Travelling has its own patterns, but (with apologies to Tolstoy) every uninspiring town is at least uninspiring in its own way. Not that Baroda is uninspiring. Not at all.

Off I go then. Ta da.

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

Do not draw my unicorn

Let us say that I believe in the Invisible Pink Unicorn. Deeply. Devoutly. I create invisible pink altars in my house, go on invisible pink pilgrimages, and believe that it is blasphemous to depict the Invisible Pink Unicorn in pictorial form.

Then one day, a newspaper brings out a cartoon depicting the Invisible Pink Unicorn. To my outrage, She is depicted as neither Invisible (obviously) nor Pink. Sacrilige. Instantly I announce rewards for the head of the cartoonist and organise demonstrations in far-off countries where much violence takes place, cars are burnt, property is destroyed. So how do you react? Was the cartoonist wrong in insulting my faith? Is my outrage justified? More importantly, is my behaviour justified?

Now, you'll no doubt say that there is a difference between Invisible Pink Unicorns and that-which-I-shall-not-dare-to-name. No doubt. It is a difference of scale, and that changes our attitude towards it, as brought out by this fine example. But the principles involved remain the same.

When I was in Lahore last week, one of my friends told me about this taxi driver he met who saved for years, took a loan, and combined the loan and the savings to buy a cab. Three weeks after he bought it, a mob burnt it down. Gogol's Overcoat, but so much worse. The poor man was speaking about committing suicide with his family. Now, however insensitive and inflammatory the Danish cartoons may have been, I do not blame them for this man's predicament. Cartoons do not kill people, people do.

Anyway, having said all that, a couple of links. First, the Economist's take on the issue, which I rather agree with. I also agree with what Glenn Reynolds has to say, especially that "[t]hese people [the protesters] are doing more to make Mohammed look bad than any cartoonist ever could." And finally, here's a piece by Flemming Rose, the editor who published those cartoons, on why he did so. At one point, he writes:

Has Jyllands-Posten insulted and disrespected Islam? It certainly didn't intend to. But what does respect mean? When I visit a mosque, I show my respect by taking off my shoes. I follow the customs, just as I do in a church, synagogue or other holy place. But if a believer demands that I, as a nonbeliever, observe his taboos in the public domain, he is not asking for my respect, but for my submission. And that is incompatible with a secular democracy.

Exactly. Worshippers of Invisible Pink Unicorns have no right to demand that submission from others. Nor does anyone else.

Update: Also, do read this old post by MadMan on tolerance.

On naming dogs, and intolerance

I've just received a letter from Naresh Fernandes, editor of that fine magazine, Time Out Mumbai, addressing an issue that I believe is of immense importance to all those of us who believe in individual freedoms. I'm reproducing the letter here, and I endorse especially strongly the last line. If you feel the same way, do take this issue up and spread the word.

Dear Editor

I’d like to call the attention of your readers to a cynical attempt by political workers to inflame religious passions in Mumbai over the last week, harnessing the eager assistance of the authorities to turn the press into the scapegoat. The chain of events went into play with the publication of a report on Feb 19 in the Times of India, detailing the arrest of one of its reporters under 295A of the IPC (deliberately injuring religious sentiments). The article says that the reporter, whom it does not identify, was arrested on the complaint of a local municipal corporator, who claimed to have taken offence at an article written one month ago about pets owned by Bollywood stars. It goes on to state that the arrest was carried out even though the paper had already apologised for details in the article that were later found to be inaccurate; the very details to which the complainant had taken offence.

A subsequent report in Mid-Day on Feb 21 casts more light on the episode. Though the Mid-Day report makes no mention of the arrest of the Times reporter, it says that the actress Manisha Koirala has been provided police protection “after her dog’s name sparked protests among Muslim fundamentalists.” The report says that “members of the community lodged a complaint at Versova police station saying that the dog’s name, Mustafa, was same as that of their spiritual head and had to be withdrawn immediately.”

While the Times management has forbidden the reporter from speaking to the press about the incident, her colleagues have identified her as Meena Iyer, a reporter on the Bollywood beat. They say that she was arrested by the plain-clothes policemen, who appeared at her home at 9 on the morning of Feb 18. At first, they even refused her permission to change out of her night-clothes and they jostled her, her colleagues say.

The episode raises troubling questions. To start with, since the report was published a month before the journalist’s arrest, the police have no real grounds for claming that it had inflamed communal passions. Instead, it is obviously the complainant who is seeking to stoke the fires. It seems baffling that the police would arrest the reporter, instead of the complainant. Considering that the police have in the past failed to act on complaints against hate speeches by such figures as Bal Thackeray, the alacrity with which they arrested Ms Iyer is perplexing.

This is further evidence the Maharashtra government’s willingness to cave in to the demands of fundamentalists, a sentiment that it demonstrated earlier in February by issuing a non-bailable warrant against the editor of the Mumbai Mirror under the same section of the IPC, for printing a photo of an allegedly offensive tattoo. The editor had to obtain anticipatory bail to avoid arrest. In January, the Maharashtra government banned the translation by American academic James Laine of a praise poem, “The Epic of Shivaji”.

Episodes like this greatly compromise our ability to effectively function as journalists, and must be countered with strong condemnation.

Yours faithfully

Naresh Fernandes

Monday, February 20, 2006

Linkaciousness begins soon

When India Uncut doesn't travel, it is largely a filter-and-perspectives blog. In other words, I link to stuff I find interesting and give my two bits. Now that I'm back in India, I'll go back to doing that, but will also try to intersperse it with more personal posts, thus thoroughly indulging myself and boring you.

In the meantime, let me share some links with you. I hardly got time to read anything during my travels, but here are a handful on links that did catch my eye.

1] Rahul Bhatia, whose joyful glow these days is surely caused either by pregnancy or facewash, writes about the loneliness of travel. I read his post at a time when I could so empathise with what he wrote about. The thing is, it's not a loneliness caused by a lack of company, but a deeper, more existential feeling, and one that merely comes to the surface when we are on the road. I'm happy to be back among loved ones, but the feeling is there somewhere, all coiled up and ready to spring loose.

2] Madhu Menon, who left a flourishing career as a tech maestro to start a restaurant, gives us "Tips on making a radical career shift." I love his beef. (No, not what you think.)

3] Sidin Vadukut, who once wrote the funniest post ever, now writes the funniest post ever. Envy comes. (Link via Gaurav.)

4] Chandrahas Choudhury writes a scathing review of Rang De Basanti. He might be shifting to Delhi soon. (The above two sentences are not necessarily related.)

And now, back to my old haunts.

To become a better writer...

.sdrawkcab gnitirw yrt...

(.egaugnal ruoy fo tuo seicnadnuder eht ekat lliw tahT)

New eyes, old eyes

Home always seems different when you return after a long time. I arrived back in Mumbai early Saturday morning after almost two months of travel, of which 42 days were spent in Pakistan, and I looked at everything here with new eyes. Marine Drive seemed sparklingly nice in the evening, all lit up and suchlike, and the city seemed so vibrant, with people on the move everywhere. There were so many options of places to eat at and things to do and magazines to buy and new TV channels to see and so on. And nicest of all, there were so many women everywhere. Why hadn’t I noticed it all these years?