India Uncut

This blog has moved to its own domain. Please visit IndiaUncut.com for the all-new India

Uncut and bookmark it. The new site has much more content and some new sections, and you can read about them here and here. You can subscribe to full RSS feeds of all the sections from here.

This blogspot site will no longer be updated, except in case of emergencies, if the main site suffers a prolonged outage. Thanks - Amit.

Saturday, January 21, 2006

The Lonely Planet legend

When I was reading up about Lahore, one of the many books I bought – yes, yes, shame on me – was Lonely Planet's guide to Pakistan. It spoke effusively of a gentleman named Malik, who runs an inn called The Regale Internet Inn. It was reputedly the best place in the city to go to for backpackers – Malik later tells me himself that it is the only one – and the gentleman reportedly takes you to the qawaali afternoons and Sufi nights I will blog about, with pictures, later.

Well, on getting to Lahore I found that a friend and fellow journalist, Mario Rodrigues of the Statesman, also had the same desire to meet him. So we figured we’d go together. I called up Mr Malik and fixed up a meeting. (This was more than a week ago.) We had a little bit of trouble finding his place, fending off the non-desire to eat in an AFC outlet, or to run into the Regal Theatre to watch a decidedly Bipasha Basu-less Jism.

Eventually we found the place, and climbed up a long flight of stairs, to be greeted effusively by Mr Malik, whose full name, we now discovered, was Malik Karamat Shams. He took us into his room, sat us down, and insisted on ordering Shawarmas for us. He struck us instantly as an inherently pleasant man, not someone being nice to us just because we were journalists. (I’ve met plenty of that kind.) Then he started talking to us about himself and how the Regale Internet Inn came to be.

Malik was the owner and editor of a progressive newspaper called Inquilab, a role he had inherited, but which he was eventually to give away. The internet was to blame, you could say.

Sometime in the mid-90s, he got a computer with an internet connection. He got it for his kids, but he soon spotted an opportunity. “The only internet connection in those days was at the British Council,” he says, “and I decided to start an internet café. If they were charging 100 rupees and hour, I decided I would charge 80. Ha ha ha.”

He soon found himself with a problem, though: the demand far outweighed the supply, as he had only one internet connection, on one computer, and many customers clamouring for his time.

Then a friend told him about networking. “He said that you can have ten computers, and only one connection. Can you believe it? So I went to my friends in the university and asked them about it, and they said, yes, it is possible. So I told them, if it is possible, then do it janaab. So they did it janaab!”

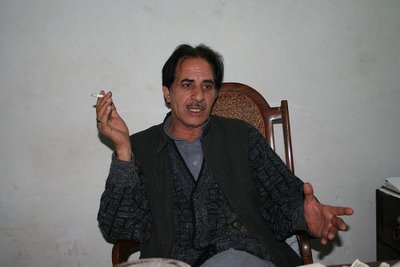

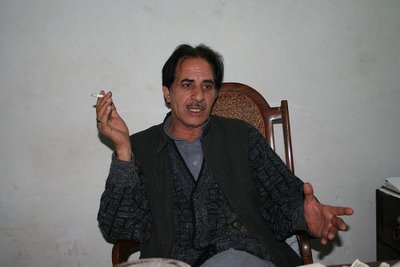

As Malik mused on life before networking, Mario allegedly started doodling. Here’s a picture.

Malik then decided that this was a business in the making, and he decided to start an internet café. Regal Cinema was nearby, and ‘Regal’ somehow, rather aptly, became ‘Regale” after he borrowed it. But he didn’t want to call it an “Internet café.” “If I put ‘café’ on the name,” he said, “people would think, there is tea available. They would come and harrass us and ask for tea. So I wanted to avoid that impression.”

Then a friend suggested that he use the word “Inn.” “I was very happy with it,” said Malik. “None of of my customers knew what it meant, and they would just see the word ‘internet’ and come.”

The “inn” part of the name soon began to cause him a little embarrasment. The office of Inquilab was still run from that building, and Malik says, “I would be sitting in my editor’s office interviewing an important personality, and these people would come and ask, is there a place to stay? Then one day Mr Brad came.”

‘Mr Brad’ was a tourist whose full name Malik does not remember, but he requested Malik that he be allowed to stay there. Malik put a prayer mat in the editor’s office, and allowed Mr Brad to stay there. There’s a picture on the wall of Malik and Mr Brad together. They look happy.

“Mr Brad stayed for a long time,” says Malik. “He made a series of documentary films, on the Pakistan film industry, on Sufi music in Pakistan society, on prostitutes.”

All these subjects interest me, and I ask Malik if he has copies of these documentaries anywhere. He laughs.

“I haven’t it seen it myself, janaab,” he says. “Even if Mr Brad wanted to send me those CDs, he wouldn’t be able to. The government does not allow us to receive CDs from abroad.”

As the days went by, more and more people came to stay, backpackers who had heard of the place through word of mouth. “It was embarrassing,” he said. “He opened up the terrace to them, allowing guests to sleep there after 9 pm as long as they left before 9 am. Eventually, Inquilab was shifted elsewhere, and all the rooms Malik had became guestrooms for backpackers: some of them dormitories, with four beds in a room. The terrace became a rite of passage for a while: if you wanted to stay in the Regale Internet Inn, you had to spend your first night on the terrace.

It wasn’t only backpackers Malik is known amongst, though. He is a big name among the musicians and artists of Pakistan. “I used to be a film journalist,” he tells me. “I became very friendly with all the struggling artists of the time. They are superstars now, but they still care for me. I can call them here, and they come and perform for me.”

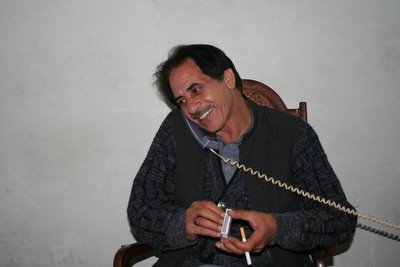

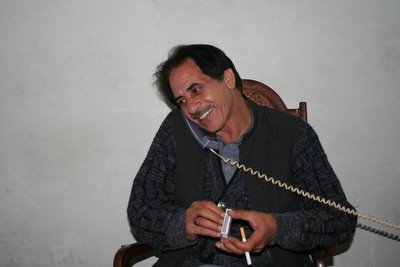

Malik now got a phone call, perhaps from one of these artists, and as he spoke on the phone, Mario, shawarma in hand, allegedly started conducting a symphony playing in his head. Here’s a picture.

Malik spoke to us about so much else that it would be impossible to detail it all here. He had once been Benazir Bhutto’s press secretary, and he spoke of how her husband’s family took such advantage of her power. “Zardari’s family had never seen power,” he told me. “They became drunk on power. Hukumat ke jhooley par pehli baar baitthey.”

He spoke about cricket. “The British Empire introduced cricket in their colonies to depoliticise society,” he told us. And then he added mysteriously, “I don’t follow cricket any more. I know the result of every game before it starts.” I ask him what will happen in this series. “Oh, we have suffered because of the earthquake,” he says, “and you will give us reason for consolation.”

The bit I am rather charmed by is when he speaks about how society is changing, and how television is responsible for it. “Pakistan society used to be much more male-dominated,” he says. “But now women are being liberated. It is all because of Star Plus.”

“Ah!” I say. “How is that?”

“You see,” he says, “there was a time – and I am nostalgic about it now – when I would go home and get my roti on time. But now I go home and my wife is watching Star Plus. I ask her for my roti, and she says, ‘drama ke baad.’ I wait, and wait, but until 10.30 I don’t get my roti. Sometimes she will get up in the breaks, do a bit of work in the kitchen, then run back when her drama starts again.”

“So is this a bad thing or a good thing?” I ask.

“Ha ha ha,” he replies. “It is a good thing for her.” But he smiles, and I sense that he is happy that she is happy. Roti can wait.

Then, like the scoundrel journalist I am, I ask, “Can you tell us which serials she likes to watch?”

“Ha ha,” he says. “Janaab, I don’t know the names.”

“Can you call up and ask please?” I say.

He bursts out laughing, and calls his wife, a wide smile on his face.

As he questions her, she becomes either shy or suspicious, and refuses to divulge the names. This amuses him further. “Tell me for which dramas you make me wait for my roti,” he booms, his eyes twinkling.

And then, to stop the teasing, she gives him one name. Kasauti Zindagi Ki. Malik laughs, and the room is filled with happiness, and love.

Well, on getting to Lahore I found that a friend and fellow journalist, Mario Rodrigues of the Statesman, also had the same desire to meet him. So we figured we’d go together. I called up Mr Malik and fixed up a meeting. (This was more than a week ago.) We had a little bit of trouble finding his place, fending off the non-desire to eat in an AFC outlet, or to run into the Regal Theatre to watch a decidedly Bipasha Basu-less Jism.

Eventually we found the place, and climbed up a long flight of stairs, to be greeted effusively by Mr Malik, whose full name, we now discovered, was Malik Karamat Shams. He took us into his room, sat us down, and insisted on ordering Shawarmas for us. He struck us instantly as an inherently pleasant man, not someone being nice to us just because we were journalists. (I’ve met plenty of that kind.) Then he started talking to us about himself and how the Regale Internet Inn came to be.

Malik was the owner and editor of a progressive newspaper called Inquilab, a role he had inherited, but which he was eventually to give away. The internet was to blame, you could say.

Sometime in the mid-90s, he got a computer with an internet connection. He got it for his kids, but he soon spotted an opportunity. “The only internet connection in those days was at the British Council,” he says, “and I decided to start an internet café. If they were charging 100 rupees and hour, I decided I would charge 80. Ha ha ha.”

He soon found himself with a problem, though: the demand far outweighed the supply, as he had only one internet connection, on one computer, and many customers clamouring for his time.

Then a friend told him about networking. “He said that you can have ten computers, and only one connection. Can you believe it? So I went to my friends in the university and asked them about it, and they said, yes, it is possible. So I told them, if it is possible, then do it janaab. So they did it janaab!”

As Malik mused on life before networking, Mario allegedly started doodling. Here’s a picture.

Malik then decided that this was a business in the making, and he decided to start an internet café. Regal Cinema was nearby, and ‘Regal’ somehow, rather aptly, became ‘Regale” after he borrowed it. But he didn’t want to call it an “Internet café.” “If I put ‘café’ on the name,” he said, “people would think, there is tea available. They would come and harrass us and ask for tea. So I wanted to avoid that impression.”

Then a friend suggested that he use the word “Inn.” “I was very happy with it,” said Malik. “None of of my customers knew what it meant, and they would just see the word ‘internet’ and come.”

The “inn” part of the name soon began to cause him a little embarrasment. The office of Inquilab was still run from that building, and Malik says, “I would be sitting in my editor’s office interviewing an important personality, and these people would come and ask, is there a place to stay? Then one day Mr Brad came.”

‘Mr Brad’ was a tourist whose full name Malik does not remember, but he requested Malik that he be allowed to stay there. Malik put a prayer mat in the editor’s office, and allowed Mr Brad to stay there. There’s a picture on the wall of Malik and Mr Brad together. They look happy.

“Mr Brad stayed for a long time,” says Malik. “He made a series of documentary films, on the Pakistan film industry, on Sufi music in Pakistan society, on prostitutes.”

All these subjects interest me, and I ask Malik if he has copies of these documentaries anywhere. He laughs.

“I haven’t it seen it myself, janaab,” he says. “Even if Mr Brad wanted to send me those CDs, he wouldn’t be able to. The government does not allow us to receive CDs from abroad.”

As the days went by, more and more people came to stay, backpackers who had heard of the place through word of mouth. “It was embarrassing,” he said. “He opened up the terrace to them, allowing guests to sleep there after 9 pm as long as they left before 9 am. Eventually, Inquilab was shifted elsewhere, and all the rooms Malik had became guestrooms for backpackers: some of them dormitories, with four beds in a room. The terrace became a rite of passage for a while: if you wanted to stay in the Regale Internet Inn, you had to spend your first night on the terrace.

It wasn’t only backpackers Malik is known amongst, though. He is a big name among the musicians and artists of Pakistan. “I used to be a film journalist,” he tells me. “I became very friendly with all the struggling artists of the time. They are superstars now, but they still care for me. I can call them here, and they come and perform for me.”

Malik now got a phone call, perhaps from one of these artists, and as he spoke on the phone, Mario, shawarma in hand, allegedly started conducting a symphony playing in his head. Here’s a picture.

Malik spoke to us about so much else that it would be impossible to detail it all here. He had once been Benazir Bhutto’s press secretary, and he spoke of how her husband’s family took such advantage of her power. “Zardari’s family had never seen power,” he told me. “They became drunk on power. Hukumat ke jhooley par pehli baar baitthey.”

He spoke about cricket. “The British Empire introduced cricket in their colonies to depoliticise society,” he told us. And then he added mysteriously, “I don’t follow cricket any more. I know the result of every game before it starts.” I ask him what will happen in this series. “Oh, we have suffered because of the earthquake,” he says, “and you will give us reason for consolation.”

The bit I am rather charmed by is when he speaks about how society is changing, and how television is responsible for it. “Pakistan society used to be much more male-dominated,” he says. “But now women are being liberated. It is all because of Star Plus.”

“Ah!” I say. “How is that?”

“You see,” he says, “there was a time – and I am nostalgic about it now – when I would go home and get my roti on time. But now I go home and my wife is watching Star Plus. I ask her for my roti, and she says, ‘drama ke baad.’ I wait, and wait, but until 10.30 I don’t get my roti. Sometimes she will get up in the breaks, do a bit of work in the kitchen, then run back when her drama starts again.”

“So is this a bad thing or a good thing?” I ask.

“Ha ha ha,” he replies. “It is a good thing for her.” But he smiles, and I sense that he is happy that she is happy. Roti can wait.

Then, like the scoundrel journalist I am, I ask, “Can you tell us which serials she likes to watch?”

“Ha ha,” he says. “Janaab, I don’t know the names.”

“Can you call up and ask please?” I say.

He bursts out laughing, and calls his wife, a wide smile on his face.

As he questions her, she becomes either shy or suspicious, and refuses to divulge the names. This amuses him further. “Tell me for which dramas you make me wait for my roti,” he booms, his eyes twinkling.

And then, to stop the teasing, she gives him one name. Kasauti Zindagi Ki. Malik laughs, and the room is filled with happiness, and love.