India Uncut

This blog has moved to its own domain. Please visit IndiaUncut.com for the all-new India

Uncut and bookmark it. The new site has much more content and some new sections, and you can read about them here and here. You can subscribe to full RSS feeds of all the sections from here.

This blogspot site will no longer be updated, except in case of emergencies, if the main site suffers a prolonged outage. Thanks - Amit.

Tuesday, January 31, 2006

It’s January 31…

… and therefore the last date for voting in the 2006 Bloggies, the Oscars of the blogworld. India Uncut has been nominated in the Best Asian Blog category, the first blog from India – indeed, from South Asia – to make the final shortlist. I’m certain this has some geopolitical significance, but I leave it to you to figure out what that is.

So if you think India Uncut deserves to win, please do go over and vote, all you need is a valid email ID. Thank you!

So if you think India Uncut deserves to win, please do go over and vote, all you need is a valid email ID. Thank you!

Monday, January 30, 2006

The exotic and the ordinary

A few months ago a friend came from out of town to visit me in Mumbai. “Show me Bombay,” he demanded. “I want to see everything: Gateway of India, Yada, Bladda, Gadda. [Those are filler words for places I don’t remember: don’t come to Mumbai and ask to see the Bladda.]”

Now, I hadn’t heard of some of these places, and hadn’t been to many of them. In almost every city I’ve lived in, I’ve been rather unfamiliar with the tourist sites. I lived in Delhi for a while, but have never seen the Qutab Minar or the Red Fort or Chandi Chowk or suchlike. So I suggested to my friend that he come to the In Orbit mall in Malad and hang out there, and other such things that I normally do. He was taken aback. He wanted the sites, not the normal stuff; the exotic, not the ordinary.

Yet, to soak in a city, I think one must eschew the exotic and revel in the everyday (though admittedly that means different things to different people, but you get what I mean). A travel writer who does not do that can mislead his readers about what a city is really like. For example, I could title the picture below “Karachi Streets” and you’d think Karachi was this quaint city full of charming vehicles like this one. But the city roads are strikingly modern, with the latest cars and SUVs and suchlike. A typical picture like that may not interest you, though.

I’ve done a bit of the exotic in Karachi – some charming Pakistani friends took me crabbing, which involves taking a boat ride from the port, going far enough into the sea so that the shore is just a tapestry of distant lights, and catching crabs, and then cooking and eating them in the boat. Utterly serene. Sadly, one is not allowed to take photographs at the port, so some striking portscapes remain in my mind’s eye.

The rest of the time, though, I’ve done ordinary things. I’ve checked out loads of shopping places, been to a rather nice mall called Park Towers (it’s Mumbai to In Orbit’s Karachi, for that sprawls a bit more) and eaten at this superb restaurant called Bar-B-Q Tonight, a massive multi-storey place where rockacious food is available. Lambiness was enjoyed.

One thing I’ve learnt, of course, is that you can’t come to a city for a week and come even close to really getting a sense of it. More time must be spent, more ordinary things done (ideally with an unjaded and keen eye). So maybe one day, when the cricket is done with, I shall come back and do just that. It’s back to the cricket now, and a run-up that goes on and on and on and … down the leg side. Jeez.

Now, I hadn’t heard of some of these places, and hadn’t been to many of them. In almost every city I’ve lived in, I’ve been rather unfamiliar with the tourist sites. I lived in Delhi for a while, but have never seen the Qutab Minar or the Red Fort or Chandi Chowk or suchlike. So I suggested to my friend that he come to the In Orbit mall in Malad and hang out there, and other such things that I normally do. He was taken aback. He wanted the sites, not the normal stuff; the exotic, not the ordinary.

Yet, to soak in a city, I think one must eschew the exotic and revel in the everyday (though admittedly that means different things to different people, but you get what I mean). A travel writer who does not do that can mislead his readers about what a city is really like. For example, I could title the picture below “Karachi Streets” and you’d think Karachi was this quaint city full of charming vehicles like this one. But the city roads are strikingly modern, with the latest cars and SUVs and suchlike. A typical picture like that may not interest you, though.

I’ve done a bit of the exotic in Karachi – some charming Pakistani friends took me crabbing, which involves taking a boat ride from the port, going far enough into the sea so that the shore is just a tapestry of distant lights, and catching crabs, and then cooking and eating them in the boat. Utterly serene. Sadly, one is not allowed to take photographs at the port, so some striking portscapes remain in my mind’s eye.

The rest of the time, though, I’ve done ordinary things. I’ve checked out loads of shopping places, been to a rather nice mall called Park Towers (it’s Mumbai to In Orbit’s Karachi, for that sprawls a bit more) and eaten at this superb restaurant called Bar-B-Q Tonight, a massive multi-storey place where rockacious food is available. Lambiness was enjoyed.

One thing I’ve learnt, of course, is that you can’t come to a city for a week and come even close to really getting a sense of it. More time must be spent, more ordinary things done (ideally with an unjaded and keen eye). So maybe one day, when the cricket is done with, I shall come back and do just that. It’s back to the cricket now, and a run-up that goes on and on and on and … down the leg side. Jeez.

Saturday, January 28, 2006

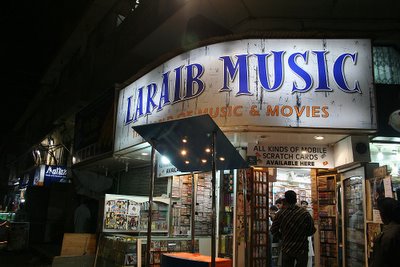

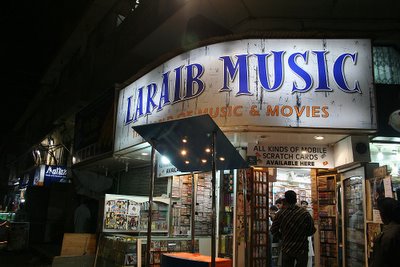

Karachi, normal

I never realised normalcy can be overwhelming, but when your expectations are of things out of the ordinary, the normal can surprise. One has heard so much about Karachi: unsafe city, teams don’t like to play here, don’t go out at night, yada yada yada. Well, at the risk of generalising, the city doesn’t seem unsafe to me at all. Last night I was out till past midnight with a charming Karachi couple, Mr and Mrs Teeth Maestro, and it felt like driving around in Mumbai or Delhi with old buddies. (And ah, Karachi’s much-spoken-of similarity to Mumbai is only in terms of weather; otherwise, the city sprawls serenly, and the roads are wider than even Delhi’s. Much rockacity.)

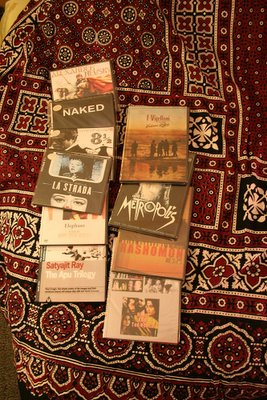

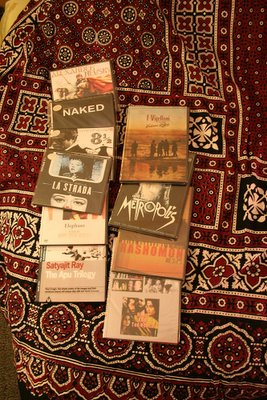

One does see a lot of cop-type people on the streets, but otherwise it doesn’t feel unsafe at all. It bustles and hustles and throbs androbs bobs, and immense fun can be had. Especially if you like movies. Many fine DVDs were bought at a fine place recommended by many noble souls, all at 100 Pakistani rupees (around 70 India rupees each). Take that.

(The DVDs above are photographed on an Ajrak presented to me -- all Indian journalists there got one each -- at a function at the press club. Joyful hospitality. Some Indian journos would have preferred booze, but not being much of a drinker myself, I was satisfied.)

At the Stadium today morning, I met up with Abdul Wahid Khan, the assistant inspector general of Sindh Police in Karachi, and Javed Ali Mahar, an assistant superintendent of police. Mr Khan was a fine, jolly man, reminding me of the onetime MD of Wisden in India, Yajurvindra Singh, both in the way he looked and in his easygoing nature. He was serious when it came to work, though.

“We have over 1500 people manning the stadium,” he told me. “We have close-circuit cameras that will capture images of every single person entering the stadium. We have yada yada and blada blada and gadda gadda. [In other words, many impressive details were given which I won’t bore you with and, wink wink, I don’t remember.]"

Afterwards, I also went and checked out the police control room. Colourful, as you can see below.

I asked Mr Khan about Karachi, and why people thought it was an unsafe city.

“Propaganda,” he boomed. “People who want Pakistan to do badly spread these lies. Karachi is a port city, and the stock market is booming, and they want to scare people away from here so that Pakistan does badly. But it is all untrue. Go out and see for yourself if it’s dangerous.”

I nodded wisely, having gone out the previous night and duly generalised. While I agreed with Mr Khan that people have the wrong impression of Karachi, I didn’t agree that there was conscious propaganda behind it. In fact, it is a common phenomenon for outsiders to believe that cities which have seen some terrorist activity are less safe than they actually are. I spent the first 12 years of my life in Chandigarh, and part of those years coincided with the terrorism in Punjab. I remember how outsiders then thought the city was terribly unsafe, but the residents felt no such thing.

The reason for this is the way the media functions. In such cities, all the crime, all the terrorist attacks and so on make news. Normalcy obviously doesn’t. All that readers from outside see reported is the bad news, and they form their impressions accordingly, and falsely. (I’m sure there is a term for this phenomenon, but I can’t remember it right now.)

Anyway, Karachi is a rocking city. Lahore also rocked, in a different way. Fun has come to Pakistan and found many cousins. Revelry, for example. Excuse me while I escort them somewhere.

One does see a lot of cop-type people on the streets, but otherwise it doesn’t feel unsafe at all. It bustles and hustles and throbs and

(The DVDs above are photographed on an Ajrak presented to me -- all Indian journalists there got one each -- at a function at the press club. Joyful hospitality. Some Indian journos would have preferred booze, but not being much of a drinker myself, I was satisfied.)

At the Stadium today morning, I met up with Abdul Wahid Khan, the assistant inspector general of Sindh Police in Karachi, and Javed Ali Mahar, an assistant superintendent of police. Mr Khan was a fine, jolly man, reminding me of the onetime MD of Wisden in India, Yajurvindra Singh, both in the way he looked and in his easygoing nature. He was serious when it came to work, though.

“We have over 1500 people manning the stadium,” he told me. “We have close-circuit cameras that will capture images of every single person entering the stadium. We have yada yada and blada blada and gadda gadda. [In other words, many impressive details were given which I won’t bore you with and, wink wink, I don’t remember.]"

Afterwards, I also went and checked out the police control room. Colourful, as you can see below.

I asked Mr Khan about Karachi, and why people thought it was an unsafe city.

“Propaganda,” he boomed. “People who want Pakistan to do badly spread these lies. Karachi is a port city, and the stock market is booming, and they want to scare people away from here so that Pakistan does badly. But it is all untrue. Go out and see for yourself if it’s dangerous.”

I nodded wisely, having gone out the previous night and duly generalised. While I agreed with Mr Khan that people have the wrong impression of Karachi, I didn’t agree that there was conscious propaganda behind it. In fact, it is a common phenomenon for outsiders to believe that cities which have seen some terrorist activity are less safe than they actually are. I spent the first 12 years of my life in Chandigarh, and part of those years coincided with the terrorism in Punjab. I remember how outsiders then thought the city was terribly unsafe, but the residents felt no such thing.

The reason for this is the way the media functions. In such cities, all the crime, all the terrorist attacks and so on make news. Normalcy obviously doesn’t. All that readers from outside see reported is the bad news, and they form their impressions accordingly, and falsely. (I’m sure there is a term for this phenomenon, but I can’t remember it right now.)

Anyway, Karachi is a rocking city. Lahore also rocked, in a different way. Fun has come to Pakistan and found many cousins. Revelry, for example. Excuse me while I escort them somewhere.

Friday, January 27, 2006

Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, 2 am

I don’t do many interviews, but very few journalists I know have conducted interviews at 2 in the morning. I had wanted to meet Rahat Fateh Ali Khan while in Faisalabad, but couldn’t make the time to do it during the days, when I had to be at the ground reporting on the cricket. His manager eventually told me that I could meet him on the evening of the last day of the game, and I was to call him in the evening. When I called him at seven, he gave me a time of 11 pm. Delays happened until I finally met the manager, Rahat’s ‘mamu’, an exceedingly pleasant gentleman named Khushnood, at around 1 am. He then insisted that I have kababs with him before we go to meet Rahat, but ordered the cook, who was roasting them on a platform by the street, not to reveal the recipe when I asked him which masalas he used in making them.

I was a little surprised at the timing of the interview, and asked him if Rahat would be awake now. “Oh yes,” he remarked, as if it was a ridiculous question to ask.

“So when does he sleep?” I asked.

“Around 10 in the morning,” he said. My eyes fairly goggled at this. Khushnood explained, “You see, he is busy giving live performances that generally happen all night. So he has to catch up with his sleep during the day.”

We proceed towards Rahat’s house, and on the way, at my request, he shows me the places where Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan , Rahat’s uncle, was born and lived and gave his first performances and so on.

, Rahat’s uncle, was born and lived and gave his first performances and so on.

(I’m reproducing snippets of my long chat with Rahat below. I needed to meet him for a longer piece I’m trying to write on qawwali music in Pakistan, and I won’t really structure this stuff out and write a piece and so on – blogs don’t demand that formal structure.

A brief backgrounder: although Rahat is in the news in India these days for ‘Jiya Dhadak Dhadak’, that superb song from Kalyug, he’s had a fairly good international career so far. He joined Nusrat’s troupe in the mid-80s, when he was just a kid, and rose to being his main side singer in the 90s. He performed with him on quite a few of his albums, and after his death in 1997, became the main singer in the group. He sang for the soundtrack of the film Four Feathers , and his first big international solo album, Rahat

, and his first big international solo album, Rahat , produced by Rick Rubin, was released in 2001.)

, produced by Rick Rubin, was released in 2001.)

* * * * *

Rahat greets me in a casual and friendly way when we meet, and orders tea. We are in an outer room of his house that is full of pictures of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan – both portraits and from performances. We start off by speaking a bit about his family and how he started learning music – as you’d expect, as a kid.

“No-one ever forced me to learn music when I was a child. In fact, I wanted to learn music, and that is why they taught me.”

Born in 1973, it was in 1980, at the age of seven, that Rahat performed on stage for the first time. It was on an occasion to mark the 15th death anniversary of his grandfather, Fatel Ali Khan, and eminences like Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, an early idol of Rahat’s, and Nusrat himself were present.

“So how was your performance received?” I ask.

Rahat laughs. “I was just a kid,” he says, “and for a kid I was pretty good, I suppose.”

* * * * *

By the time Rahat joined his uncle’s troupe, in the mid-1980s, Nusrat was already a virtual legend in his own country. He was also a much criticised man, and the reasons for both the laudings and the lashings he received were the same: what he did with the form of the qawaali.

“Unhone ek guldasta banaaya,” says Rahat. “Usme qawwali, thumri, ghazal, muktalif kism ki musical forms ko shaamil kiya.” Nusrat made a bouquet of musical styles, but unlike what the purists say, he did not compromise while doing that. “Everthing he did retained the flavour of qawwali,” says Rahat. The essence of his music, in other words, drew from the same spiritual yearning that marks out qawwali music.

One of the biggest gripes around Nusrat – and, indeed, against Rahat today – is that he demeaned qawwali music by taking it out of its original setting of dargahs and suchlike, and into marriage functions and Bollywood. I ask Rahat about that, about how one can reconcile the original intent of qawwali as a spiritual tool with its use today for entertainment.

“You can listen to every qawwali in two ways,” he tells me. “When we sing of ‘sharaab’ and ‘suroor’, you can take the meaning to be either literal, or a metaphor for something spiritual. It depends on the person listening to it, not on the setting.”

* * * * *

In 1985, Nusrat performed at a festival in Cornwall, and that is where the West sat up and took notice of him. As the years went by, collaborations, albums and concerts followed, most notably his remarkable series of albums with Real World.

“Did he adapt his music for Western Audiences?” I ask Rahat. “Was there a difference between the music he performed in Pakistan and that abroad?”

“There had to be,” says Rahat. “The music he performed abroad had much more of classical content. Foreigners didn’t understand our language and our lyrics, so the music had to work harder.”

Also, if I may speculate, foreigners unused to classical music were likely to be far more impressed by meandering alaaps than local audiences, who had seen plenty of that stuff, and whose expectations from the music were often different. In other words, Nusrat perhaps played to his Western audiences a bit, gave them the exotica he craved – but always without compromising the essence of his music.

I ask Rahat about Star Rise , the Real World compilation of some of Nusrat’s music remixed by stars of the Asian Underground. It’s the only work featuring Nusrat’s voice that I simply can’t stand, and I ask Rahat what Nusrat thought of such remixes. Rahat laughs. “Nusrat hated it,” he says. “He felt they had destroyed his music.”

, the Real World compilation of some of Nusrat’s music remixed by stars of the Asian Underground. It’s the only work featuring Nusrat’s voice that I simply can’t stand, and I ask Rahat what Nusrat thought of such remixes. Rahat laughs. “Nusrat hated it,” he says. “He felt they had destroyed his music.”

* * * * *

I ask him about his album, Rahat

I ask him about his album, Rahat , which was produced by Rick Rubin and released by Sony in 2001. “Your voice sounds very different in that than it does in some of the stuff you’ve recently done,” I say, “like ‘Jiya Dhadak Dhadak’. Why is that?”

, which was produced by Rick Rubin and released by Sony in 2001. “Your voice sounds very different in that than it does in some of the stuff you’ve recently done,” I say, “like ‘Jiya Dhadak Dhadak’. Why is that?”

Rahat laughs. “Rick came to me and he said that he wanted to use these four tracks that I’d recorded in 1996. I told him that I’ve changed since then, I’m a different singer now. I offered to sing those same songs for him again today. But he insisted on using those songs, he said that that is how he wanted to project me.”

“And how have you changed?” I asked.

“Oh, I’m much better now, I was so young then. [He was 23 in 1996.] I’ve learnt so much more, I can do a lot more with my voice now. Then, I couldn’t pull off everything I could conceive.”

“Can you do that now?”

“No. I’m not sure I ever will.”

“Could Nusrat do it.”

“Oh yes.” Rahat smiles, remembering. “He could do anything.”

* * * * *

Rahat has performed with Eddie Vedder at the Central park in New York, and with Pearl Jam at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, where they performed “Long Road” together, the song from the soundtrack of Dead Man Walking

Rahat has performed with Eddie Vedder at the Central park in New York, and with Pearl Jam at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, where they performed “Long Road” together, the song from the soundtrack of Dead Man Walking , for which Nusrat had collaborated with Pearl Jam. Rahat had participated in the recording of that.

, for which Nusrat had collaborated with Pearl Jam. Rahat had participated in the recording of that.

“The recording was in a small room, not the kind of big studio we had expected. And when these guys came, holding guitars, we thought they must be musicians. I was surprised when Eddie started singing while recording, I had thought till then he was just a musician, playing guitar.”

“And how did you find his singing?” I ask.

“Oh, when he started singing, I couldn’t make anything out, we all had headphones on. But later, when I heard the track, I was amazed. He sounded so good!”

* * * * *

There is fierce competition among qawwali singers, Rahat tells me, which comes through in the format of the performances.

“When a group performs,” says Rahat, “it is understood that it doesn’t get up as long as the audience wants it to go on. So if two groups are scheduled to perform on one night, the first one will try to make sure that it pleases the audience, so that the second one can’t get on stage.

“So many times,” he continues with a smile, “Khansaab would perform so well that the people scheduled to perform after him never got a chance to come on stage.

“It is like a muqabla.”

* * * * *

Rahat isn’t just a singer, an interpreter, but also a composer, a creator. “I compose around 30-40 songs every year,” he tells me.

“Do you keep audiences in mind when you do this,” I ask, “or do you just create the kind of music that makes you happy?”

“Oh, I have to keep audiences in mind,” he says. “For example, if there is a fashion for Raga Bhairavi, I’ll sit down with that and create songs in it.”

After composing his music, Rahat tests them out among audiences. He gives between 20 to 25 live performances every month, and he plays his new songs at the concerts. “The ones which receive a good response stay in my repertoire,” he says. “The others I just drop. One has to go down to the level of the audience.”

“Can’t you lift the audience to your level?” I ask.

“No,” he says.

* * * *

Just before I leave I ask him if he would have been such an accomplished musician if he wasn’t from this family.

“No,” he says emphatically. “I would have been just another ordinary singer.”

I was a little surprised at the timing of the interview, and asked him if Rahat would be awake now. “Oh yes,” he remarked, as if it was a ridiculous question to ask.

“So when does he sleep?” I asked.

“Around 10 in the morning,” he said. My eyes fairly goggled at this. Khushnood explained, “You see, he is busy giving live performances that generally happen all night. So he has to catch up with his sleep during the day.”

We proceed towards Rahat’s house, and on the way, at my request, he shows me the places where Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

(I’m reproducing snippets of my long chat with Rahat below. I needed to meet him for a longer piece I’m trying to write on qawwali music in Pakistan, and I won’t really structure this stuff out and write a piece and so on – blogs don’t demand that formal structure.

A brief backgrounder: although Rahat is in the news in India these days for ‘Jiya Dhadak Dhadak’, that superb song from Kalyug, he’s had a fairly good international career so far. He joined Nusrat’s troupe in the mid-80s, when he was just a kid, and rose to being his main side singer in the 90s. He performed with him on quite a few of his albums, and after his death in 1997, became the main singer in the group. He sang for the soundtrack of the film Four Feathers

* * * * *

Rahat greets me in a casual and friendly way when we meet, and orders tea. We are in an outer room of his house that is full of pictures of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan – both portraits and from performances. We start off by speaking a bit about his family and how he started learning music – as you’d expect, as a kid.

“No-one ever forced me to learn music when I was a child. In fact, I wanted to learn music, and that is why they taught me.”

Born in 1973, it was in 1980, at the age of seven, that Rahat performed on stage for the first time. It was on an occasion to mark the 15th death anniversary of his grandfather, Fatel Ali Khan, and eminences like Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, an early idol of Rahat’s, and Nusrat himself were present.

“So how was your performance received?” I ask.

Rahat laughs. “I was just a kid,” he says, “and for a kid I was pretty good, I suppose.”

* * * * *

By the time Rahat joined his uncle’s troupe, in the mid-1980s, Nusrat was already a virtual legend in his own country. He was also a much criticised man, and the reasons for both the laudings and the lashings he received were the same: what he did with the form of the qawaali.

“Unhone ek guldasta banaaya,” says Rahat. “Usme qawwali, thumri, ghazal, muktalif kism ki musical forms ko shaamil kiya.” Nusrat made a bouquet of musical styles, but unlike what the purists say, he did not compromise while doing that. “Everthing he did retained the flavour of qawwali,” says Rahat. The essence of his music, in other words, drew from the same spiritual yearning that marks out qawwali music.

One of the biggest gripes around Nusrat – and, indeed, against Rahat today – is that he demeaned qawwali music by taking it out of its original setting of dargahs and suchlike, and into marriage functions and Bollywood. I ask Rahat about that, about how one can reconcile the original intent of qawwali as a spiritual tool with its use today for entertainment.

“You can listen to every qawwali in two ways,” he tells me. “When we sing of ‘sharaab’ and ‘suroor’, you can take the meaning to be either literal, or a metaphor for something spiritual. It depends on the person listening to it, not on the setting.”

* * * * *

In 1985, Nusrat performed at a festival in Cornwall, and that is where the West sat up and took notice of him. As the years went by, collaborations, albums and concerts followed, most notably his remarkable series of albums with Real World.

“Did he adapt his music for Western Audiences?” I ask Rahat. “Was there a difference between the music he performed in Pakistan and that abroad?”

“There had to be,” says Rahat. “The music he performed abroad had much more of classical content. Foreigners didn’t understand our language and our lyrics, so the music had to work harder.”

Also, if I may speculate, foreigners unused to classical music were likely to be far more impressed by meandering alaaps than local audiences, who had seen plenty of that stuff, and whose expectations from the music were often different. In other words, Nusrat perhaps played to his Western audiences a bit, gave them the exotica he craved – but always without compromising the essence of his music.

I ask Rahat about Star Rise

* * * * *

I ask him about his album, Rahat

I ask him about his album, RahatRahat laughs. “Rick came to me and he said that he wanted to use these four tracks that I’d recorded in 1996. I told him that I’ve changed since then, I’m a different singer now. I offered to sing those same songs for him again today. But he insisted on using those songs, he said that that is how he wanted to project me.”

“And how have you changed?” I asked.

“Oh, I’m much better now, I was so young then. [He was 23 in 1996.] I’ve learnt so much more, I can do a lot more with my voice now. Then, I couldn’t pull off everything I could conceive.”

“Can you do that now?”

“No. I’m not sure I ever will.”

“Could Nusrat do it.”

“Oh yes.” Rahat smiles, remembering. “He could do anything.”

* * * * *

Rahat has performed with Eddie Vedder at the Central park in New York, and with Pearl Jam at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, where they performed “Long Road” together, the song from the soundtrack of Dead Man Walking

Rahat has performed with Eddie Vedder at the Central park in New York, and with Pearl Jam at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, where they performed “Long Road” together, the song from the soundtrack of Dead Man Walking“The recording was in a small room, not the kind of big studio we had expected. And when these guys came, holding guitars, we thought they must be musicians. I was surprised when Eddie started singing while recording, I had thought till then he was just a musician, playing guitar.”

“And how did you find his singing?” I ask.

“Oh, when he started singing, I couldn’t make anything out, we all had headphones on. But later, when I heard the track, I was amazed. He sounded so good!”

* * * * *

There is fierce competition among qawwali singers, Rahat tells me, which comes through in the format of the performances.

“When a group performs,” says Rahat, “it is understood that it doesn’t get up as long as the audience wants it to go on. So if two groups are scheduled to perform on one night, the first one will try to make sure that it pleases the audience, so that the second one can’t get on stage.

“So many times,” he continues with a smile, “Khansaab would perform so well that the people scheduled to perform after him never got a chance to come on stage.

“It is like a muqabla.”

* * * * *

Rahat isn’t just a singer, an interpreter, but also a composer, a creator. “I compose around 30-40 songs every year,” he tells me.

“Do you keep audiences in mind when you do this,” I ask, “or do you just create the kind of music that makes you happy?”

“Oh, I have to keep audiences in mind,” he says. “For example, if there is a fashion for Raga Bhairavi, I’ll sit down with that and create songs in it.”

After composing his music, Rahat tests them out among audiences. He gives between 20 to 25 live performances every month, and he plays his new songs at the concerts. “The ones which receive a good response stay in my repertoire,” he says. “The others I just drop. One has to go down to the level of the audience.”

“Can’t you lift the audience to your level?” I ask.

“No,” he says.

* * * *

Just before I leave I ask him if he would have been such an accomplished musician if he wasn’t from this family.

“No,” he says emphatically. “I would have been just another ordinary singer.”

Yeh jo halka halka saroor hai

Room service

Overheard in my hotel room at Karachi:

My room-mate: Hello, room service?

Disembodied voice: Yes.

Room-mate: I'm calling from room 225, can you help me with potty, please?

Voice: Certainly sir. For one person or two persons?

Half-an-hour later, pot tea came.

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

Scenes from a stadium

Damn, these tours are so tiring. Normally, during cricket tours, one gets time to work on pieces in the press box during the day, but because of my hourly radio updates for BBC, at which I'm sort of struggling, I don’t have time to work on anything else. And by the time I finish my daily Guardian report in the evening I'm rather tired and unfresh. So I have loads of material collected from Lahore, but no time to write the features I’m planning. Hardly any time for blogging, either, though I did get a few posts about Lahore done over the weekend. So, until I find more interesting things to blog about, here are some pictures from the ground.

First, the press box. It’s just over a right-hander’s long-off at the Golf Club End and is open at the front. The view from it is great, but the sunshine at the front sometimes gets a bit harsh, and I can barely work on my laptop in the first half of the day because I can’t see anything on the screen. For those who don’t have laptops or haven’t taken telephone lines, there are a few computers at the back of the room where one can sit and surf and file.

The most important person in any press box, bar none, is the scorer. At every dismissal and landmark he sits down and reels off the relevant stats on his microphone: so many minutes, so many balls etc. He also has a walkie-talkie to communicate with scorers in other parts of the ground. He has to watch every single ball. It’s a heck of a job, and in many places voluntary or very poorly paid. Most scorers do it just for the love of cricket, to be a part of the game they love.

Faisalabad may be a sleepy town, but the crowds here rock. We’ve had a packed house from the second day onwards, and not only do they have a lot of fun, they’re also very bipartisan. Yesterday, when Rahul Dravid was on 99, slow handclaps urged him to his century and loud applause greeted the shot that got him there. There was loud spontaneous applause today when Yuvraj Singh pulled off a diving save. At one point today, when the grizzled occupants of the press box were close to sleep, a section of the crowd entertained itself by throwing a man up in the air again and again, presumably with his consent, as if it was a Pearl Jam concert. Fun came.

Sometimes I feel so old and cynical, and nothing seems to excite me. And then I think of the childlike joy with which I once watched the game. It comes sometimes, in fleeting moments, and then it passes, as all things must and all that.

After the game, there’s a press conference in front of the sightscreen at the other end of the stadium. We walk across the ground, over the same turf where for hours today these men have done battle. Often, the players do cooling-down exercises on the ground, and an enterprising television journalist will invariably take the opportunity to use that as a background for his piece-to-camera. Apart from the main presser, some persistent journalists often get a quote or two from a coach or player standing by.

I like the way the ground looks in the evening: as journalists finish their copy in the press box, a tranquil calm descends on this fierce arena. (Well, look, it’s supposed to be fierce, but with a pitch like this…)

The Indian team doesn’t have much of a chance to catch the sights. A ring of security escorts them from ground to bus to hotel. Such is international cricket.

(Click on pics to enlarge.)

Monday, January 23, 2006

The Bloggies

I'm delighted to inform you that just a few days after winning the IndiBlog of the Year award, India Uncut has now been nominated for the prestigious Bloggies, in the Best Asian Weblog category. This is the only South Asian blog among the five finalists, and I guess that's an honour in itself. Thank you to all those of you who voted for me in the first phase of voting and made this possible. If you feel my blog deserves it, please do help me win this one by voting here. Hurry, voting's on for a just a limited period of time!

Back to work now.

Sunday, January 22, 2006

Sufi night

After an interesting afternoon spent listening to qawwalis (chronicled here and here), Swati, Furqan and I head on over to Regale Internet Inn, from where Malik is going to take us to the famous Sufi night, which takes place every Thursday at the shrine of Baba Shah Jamal. There are two quadrangles in this shrine: In one, the famous Pappu Saeen plays dhol, while in the other, Goonga Saeen and Mithu Saeen play dhol. (Goonga is deaf!) These chaps play furiously for hours, and in the middle of their performance, dervishes come and spin around madly, as the audience gets high on the music, the spinning and lots of charas and suchlike.

As we are on our way, Swati gets a call from Malik, who says that a French Television crew will also be there, and they have paid 50,000 Pakistani rupees to Mithu Saeen to see him perform. To avoid the possibility of him demanding money from NDTV, Malik has told him that we are students from the National College of Art in Lahore. This alarms us a bit, and we wonder if it is necessary. Then we reach Regale Internet Inn and meet Mithu Saeen.

Mithu asks Malik gruffly if there is any money in this for him. Malik tells him that we’re just students. He looks at us suspiciously. Malik diverts his attention by asking him to show the money he’s been given by the French team. He takes out a bundle of dollars from his pocket. He looks at the money, and then at us. (My still camera isn't an issue, but as I'm with Swati and Furqan, I'm seen as part of the TV crew. In any case, I do want the guys to get their story.)

Malik hustles and bustles us out the door, and we drive down to the lane where the shrine is located.

Before the event, the dhol players and a few hangers on sit inside a smoky room by the road, as we wait outside. Swati contemplates the meaning of life while Furqan contemplates the camera.

Then we head inside the shrine, shoes in hand, jostling through a busy bunch of people. As the evening proceeds, I realise that the audience consists of essentially two kinds of people: some foreigners who are here for the exotica; and many localites who are here to dope and space out. We don’t dope, so you know which category we’re in.

Goonga Saeen and Mithu Saeen then get going on their dhols. It’s percussion played at a furious pace, with a hypnotic rhythm to it that would numb the senses if you succumbed to it. They play incredibly well together, and Goonga seems quite at ease, while Mithu often seems to be hard at work, concentrating intently. They’re perfectly in synch all through, though, and this is probably dhol heaven for those who have a taste for the stuff. (I don’t think I do, I must confess.)

After an hour or so of frenetic dholing, the crowd at the front moves back, and dervishes take the floor. The place is abuzz now, and people are already lighting up.

The dervishes now begin to whirl madly, round and round and round and round, without stopping. They spin and shake and shiver, they whirl and vibrate, they fill the place with so much mad energy that I feel dizzy myself, even though I’m sitting on the ground.

Don’t imagine that NDTV is doing nothing. Furqan is also spinning madly in his own way, taking shots of this and that and everything else.

Later, when we’ve had enough, we take Malik out on the road for some soundbytes.

I take photographs, and the one below is an apt one when you consider that the location is just outside a Sufi shrine. I’d set exposure to the levels of the street, but Malik had a camera light trained on his face, and it made him look as if he was an otherworldly body of light. Such fun.

As Malik is finishing giving his bytes, I hang around at the other side of the street. A couple of chaps then come and stand menacingly from either side of me. “Are you from India?” asks one of them.

I’m suddenly a bit worried, given the crowd that hangs around here, and the way these guys are looking at me. “Er, yes, I say.”

“And are you Muslim?” asks the chap, a touch of menace in his voice. I’m suddenly, for the only time on this delightful trip and just for a few seconds, terrified. “Yes,” I reply. He asks me my name. I reply:

“Arif Khan.”

Overheard in my hotel room at Karachi:

My room-mate: Hello, room service?Half-an-hour later, pot tea came.

Disembodied voice: Yes.

Room-mate: I'm calling from room 225, can you help me with potty, please?

Voice: Certainly sir. For one person or two persons?

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

Damn, these tours are so tiring. Normally, during cricket tours, one gets time to work on pieces in the press box during the day, but because of my hourly radio updates for BBC, at which I'm sort of struggling, I don’t have time to work on anything else. And by the time I finish my daily Guardian report in the evening I'm rather tired and unfresh. So I have loads of material collected from Lahore, but no time to write the features I’m planning. Hardly any time for blogging, either, though I did get a few posts about Lahore done over the weekend. So, until I find more interesting things to blog about, here are some pictures from the ground.

First, the press box. It’s just over a right-hander’s long-off at the Golf Club End and is open at the front. The view from it is great, but the sunshine at the front sometimes gets a bit harsh, and I can barely work on my laptop in the first half of the day because I can’t see anything on the screen. For those who don’t have laptops or haven’t taken telephone lines, there are a few computers at the back of the room where one can sit and surf and file.

The most important person in any press box, bar none, is the scorer. At every dismissal and landmark he sits down and reels off the relevant stats on his microphone: so many minutes, so many balls etc. He also has a walkie-talkie to communicate with scorers in other parts of the ground. He has to watch every single ball. It’s a heck of a job, and in many places voluntary or very poorly paid. Most scorers do it just for the love of cricket, to be a part of the game they love.

Faisalabad may be a sleepy town, but the crowds here rock. We’ve had a packed house from the second day onwards, and not only do they have a lot of fun, they’re also very bipartisan. Yesterday, when Rahul Dravid was on 99, slow handclaps urged him to his century and loud applause greeted the shot that got him there. There was loud spontaneous applause today when Yuvraj Singh pulled off a diving save. At one point today, when the grizzled occupants of the press box were close to sleep, a section of the crowd entertained itself by throwing a man up in the air again and again, presumably with his consent, as if it was a Pearl Jam concert. Fun came.

Sometimes I feel so old and cynical, and nothing seems to excite me. And then I think of the childlike joy with which I once watched the game. It comes sometimes, in fleeting moments, and then it passes, as all things must and all that.

After the game, there’s a press conference in front of the sightscreen at the other end of the stadium. We walk across the ground, over the same turf where for hours today these men have done battle. Often, the players do cooling-down exercises on the ground, and an enterprising television journalist will invariably take the opportunity to use that as a background for his piece-to-camera. Apart from the main presser, some persistent journalists often get a quote or two from a coach or player standing by.

I like the way the ground looks in the evening: as journalists finish their copy in the press box, a tranquil calm descends on this fierce arena. (Well, look, it’s supposed to be fierce, but with a pitch like this…)

The Indian team doesn’t have much of a chance to catch the sights. A ring of security escorts them from ground to bus to hotel. Such is international cricket.

(Click on pics to enlarge.)

First, the press box. It’s just over a right-hander’s long-off at the Golf Club End and is open at the front. The view from it is great, but the sunshine at the front sometimes gets a bit harsh, and I can barely work on my laptop in the first half of the day because I can’t see anything on the screen. For those who don’t have laptops or haven’t taken telephone lines, there are a few computers at the back of the room where one can sit and surf and file.

The most important person in any press box, bar none, is the scorer. At every dismissal and landmark he sits down and reels off the relevant stats on his microphone: so many minutes, so many balls etc. He also has a walkie-talkie to communicate with scorers in other parts of the ground. He has to watch every single ball. It’s a heck of a job, and in many places voluntary or very poorly paid. Most scorers do it just for the love of cricket, to be a part of the game they love.

Faisalabad may be a sleepy town, but the crowds here rock. We’ve had a packed house from the second day onwards, and not only do they have a lot of fun, they’re also very bipartisan. Yesterday, when Rahul Dravid was on 99, slow handclaps urged him to his century and loud applause greeted the shot that got him there. There was loud spontaneous applause today when Yuvraj Singh pulled off a diving save. At one point today, when the grizzled occupants of the press box were close to sleep, a section of the crowd entertained itself by throwing a man up in the air again and again, presumably with his consent, as if it was a Pearl Jam concert. Fun came.

Sometimes I feel so old and cynical, and nothing seems to excite me. And then I think of the childlike joy with which I once watched the game. It comes sometimes, in fleeting moments, and then it passes, as all things must and all that.

After the game, there’s a press conference in front of the sightscreen at the other end of the stadium. We walk across the ground, over the same turf where for hours today these men have done battle. Often, the players do cooling-down exercises on the ground, and an enterprising television journalist will invariably take the opportunity to use that as a background for his piece-to-camera. Apart from the main presser, some persistent journalists often get a quote or two from a coach or player standing by.

I like the way the ground looks in the evening: as journalists finish their copy in the press box, a tranquil calm descends on this fierce arena. (Well, look, it’s supposed to be fierce, but with a pitch like this…)

The Indian team doesn’t have much of a chance to catch the sights. A ring of security escorts them from ground to bus to hotel. Such is international cricket.

(Click on pics to enlarge.)

Monday, January 23, 2006

I'm delighted to inform you that just a few days after winning the IndiBlog of the Year award, India Uncut has now been nominated for the prestigious Bloggies, in the Best Asian Weblog category. This is the only South Asian blog among the five finalists, and I guess that's an honour in itself. Thank you to all those of you who voted for me in the first phase of voting and made this possible. If you feel my blog deserves it, please do help me win this one by voting here. Hurry, voting's on for a just a limited period of time!

Back to work now.

Back to work now.

Sunday, January 22, 2006

After an interesting afternoon spent listening to qawwalis (chronicled here and here), Swati, Furqan and I head on over to Regale Internet Inn, from where Malik is going to take us to the famous Sufi night, which takes place every Thursday at the shrine of Baba Shah Jamal. There are two quadrangles in this shrine: In one, the famous Pappu Saeen plays dhol, while in the other, Goonga Saeen and Mithu Saeen play dhol. (Goonga is deaf!) These chaps play furiously for hours, and in the middle of their performance, dervishes come and spin around madly, as the audience gets high on the music, the spinning and lots of charas and suchlike.

As we are on our way, Swati gets a call from Malik, who says that a French Television crew will also be there, and they have paid 50,000 Pakistani rupees to Mithu Saeen to see him perform. To avoid the possibility of him demanding money from NDTV, Malik has told him that we are students from the National College of Art in Lahore. This alarms us a bit, and we wonder if it is necessary. Then we reach Regale Internet Inn and meet Mithu Saeen.

Mithu asks Malik gruffly if there is any money in this for him. Malik tells him that we’re just students. He looks at us suspiciously. Malik diverts his attention by asking him to show the money he’s been given by the French team. He takes out a bundle of dollars from his pocket. He looks at the money, and then at us. (My still camera isn't an issue, but as I'm with Swati and Furqan, I'm seen as part of the TV crew. In any case, I do want the guys to get their story.)

Malik hustles and bustles us out the door, and we drive down to the lane where the shrine is located.

Before the event, the dhol players and a few hangers on sit inside a smoky room by the road, as we wait outside. Swati contemplates the meaning of life while Furqan contemplates the camera.

Then we head inside the shrine, shoes in hand, jostling through a busy bunch of people. As the evening proceeds, I realise that the audience consists of essentially two kinds of people: some foreigners who are here for the exotica; and many localites who are here to dope and space out. We don’t dope, so you know which category we’re in.

Goonga Saeen and Mithu Saeen then get going on their dhols. It’s percussion played at a furious pace, with a hypnotic rhythm to it that would numb the senses if you succumbed to it. They play incredibly well together, and Goonga seems quite at ease, while Mithu often seems to be hard at work, concentrating intently. They’re perfectly in synch all through, though, and this is probably dhol heaven for those who have a taste for the stuff. (I don’t think I do, I must confess.)

After an hour or so of frenetic dholing, the crowd at the front moves back, and dervishes take the floor. The place is abuzz now, and people are already lighting up.

The dervishes now begin to whirl madly, round and round and round and round, without stopping. They spin and shake and shiver, they whirl and vibrate, they fill the place with so much mad energy that I feel dizzy myself, even though I’m sitting on the ground.

Don’t imagine that NDTV is doing nothing. Furqan is also spinning madly in his own way, taking shots of this and that and everything else.

Later, when we’ve had enough, we take Malik out on the road for some soundbytes.

I take photographs, and the one below is an apt one when you consider that the location is just outside a Sufi shrine. I’d set exposure to the levels of the street, but Malik had a camera light trained on his face, and it made him look as if he was an otherworldly body of light. Such fun.

As Malik is finishing giving his bytes, I hang around at the other side of the street. A couple of chaps then come and stand menacingly from either side of me. “Are you from India?” asks one of them.

I’m suddenly a bit worried, given the crowd that hangs around here, and the way these guys are looking at me. “Er, yes, I say.”

“And are you Muslim?” asks the chap, a touch of menace in his voice. I’m suddenly, for the only time on this delightful trip and just for a few seconds, terrified. “Yes,” I reply. He asks me my name. I reply:

“Arif Khan.”

As we are on our way, Swati gets a call from Malik, who says that a French Television crew will also be there, and they have paid 50,000 Pakistani rupees to Mithu Saeen to see him perform. To avoid the possibility of him demanding money from NDTV, Malik has told him that we are students from the National College of Art in Lahore. This alarms us a bit, and we wonder if it is necessary. Then we reach Regale Internet Inn and meet Mithu Saeen.

Mithu asks Malik gruffly if there is any money in this for him. Malik tells him that we’re just students. He looks at us suspiciously. Malik diverts his attention by asking him to show the money he’s been given by the French team. He takes out a bundle of dollars from his pocket. He looks at the money, and then at us. (My still camera isn't an issue, but as I'm with Swati and Furqan, I'm seen as part of the TV crew. In any case, I do want the guys to get their story.)

Malik hustles and bustles us out the door, and we drive down to the lane where the shrine is located.

Before the event, the dhol players and a few hangers on sit inside a smoky room by the road, as we wait outside. Swati contemplates the meaning of life while Furqan contemplates the camera.

Then we head inside the shrine, shoes in hand, jostling through a busy bunch of people. As the evening proceeds, I realise that the audience consists of essentially two kinds of people: some foreigners who are here for the exotica; and many localites who are here to dope and space out. We don’t dope, so you know which category we’re in.

Goonga Saeen and Mithu Saeen then get going on their dhols. It’s percussion played at a furious pace, with a hypnotic rhythm to it that would numb the senses if you succumbed to it. They play incredibly well together, and Goonga seems quite at ease, while Mithu often seems to be hard at work, concentrating intently. They’re perfectly in synch all through, though, and this is probably dhol heaven for those who have a taste for the stuff. (I don’t think I do, I must confess.)

After an hour or so of frenetic dholing, the crowd at the front moves back, and dervishes take the floor. The place is abuzz now, and people are already lighting up.

The dervishes now begin to whirl madly, round and round and round and round, without stopping. They spin and shake and shiver, they whirl and vibrate, they fill the place with so much mad energy that I feel dizzy myself, even though I’m sitting on the ground.

Don’t imagine that NDTV is doing nothing. Furqan is also spinning madly in his own way, taking shots of this and that and everything else.

Later, when we’ve had enough, we take Malik out on the road for some soundbytes.

I take photographs, and the one below is an apt one when you consider that the location is just outside a Sufi shrine. I’d set exposure to the levels of the street, but Malik had a camera light trained on his face, and it made him look as if he was an otherworldly body of light. Such fun.

As Malik is finishing giving his bytes, I hang around at the other side of the street. A couple of chaps then come and stand menacingly from either side of me. “Are you from India?” asks one of them.

I’m suddenly a bit worried, given the crowd that hangs around here, and the way these guys are looking at me. “Er, yes, I say.”

“And are you Muslim?” asks the chap, a touch of menace in his voice. I’m suddenly, for the only time on this delightful trip and just for a few seconds, terrified. “Yes,” I reply. He asks me my name. I reply:

“Arif Khan.”